The following is from the Denkôroku, the collection of enlightenment accounts of the succession of Soto Ancestors from the Buddha on up to Dogen and his immediate successors. It was written by Keizan, the third generation successor after Dogen, and the second great ancestor in the Japanese Soto tradition. The narrative and Keizan’s comments are in bold type; my own comments are in regular type.

PART ONE

He worked in the ricehulling quarter of Ôbai.

(Ôbai is the name of the mountain on which Daiman Zenji’s monastery is located. Throughout this story, in accord with the custom of the time, the word is used interchangeably with “Daiman Zenji” to refer to the master of the mountain, the Fifth Ancestor, as well as to the mountain itself.)

(One day), Daiman Zenji entered the quarter in the night and, instructing, said, “Has the rice become white yet?” The master said, “It has become white, but it hasn’t been sifted yet.” Daiman struck the mortar (in which the rice was hulled) three times with his stick. The master tossed the rice in the winnow three times and entered the Patriarch’s room.

BACKGROUND

The master’s family name was Ro. His ancestors were from Han’yô. His father was (named) Gyôtô. During the Era of Butoku (618-626) he was demoted and sent to Shinshû in the South-Sea [=Nankai] Region. He finally settled there. (The master’s) father died, and (the master’s) mother kept the father’s will and took care (of the master). As (the master) was growing, the family was extremely poor and the master earned a living cutting firewood. One day he came to the city with a bundle of firewood, and he heard a customer reciting the Diamond Sutra. When the customer reached the line where it said, “Dwelling nowhere, Mind comes forth,” (the master) was struck and enlightened.

He asked the customer, “What sutra is that? From whom did you get it?” The customer replied, “This is named the Diamond Sutra, and I got it from the Great Master Nin at Ôbai.”

(“Nin” or “Kônin” is the Fifth Patriarch, namely Daiman Zenji.)

The master immediately told his mother about his intention to look for a master for the Dharma. He came directly to Shôshû and encountered a dignified man named Ryû-Shiryaku, and they became close friends. The nun Mujinzô was Shiryaku’s mother-in-law and was always reciting the Nirvana Sutra. The master listened to her for a while and then told her its meaning. Then, the nun took a scroll and asked about some words. The master said, “I can’t read the characters, but please ask me the meaning.” The nun said, “You can’t read the characters, how can you know their meaning?” The master said, “The delicate principles of all buddhas have nothing to do with characters.” The nun marveled at this and told the village elders, saying, “Nô (Enô)is a man of the Way. We ought to ask (him to stay here) and venerate and support him.” So, the people competed to come to him and greet him with deep respect.

(That is, they treated him as an authentic teacher, even though he was teaching only on his own authority, unauthenticated by any teacher lineage, highly unusual in a society in which lineage is of such great importance.)

There was an old temple nearby by the name of Hôrin. The people discussed among themselves and repaired the temple, and they made the master stay there. The four groups (of male and female monastics and laymen and laywomen) gathered like clouds. It quickly became an outstanding Dharma place. One day, the master suddenly said to himself, “I am seeking the great Dharma. Why should I stop halfway?”

(… like Joshu, who at the age of sixty also put aside the respect and veneration paid him by the monks of Nansen’s temple, who had expected that he would stay and take over the temple upon Nansen’s death, to go on pilgrimage in order to deepen his realization by engaging in “Dharma Combat” with other masters.)

He left the next day and went to the western cave area of Gakushô District. There he met Zen Master Chion, whom he asked for instruction. Chion said, “When I look at you, I see a fresh and outstanding quality, not quite like that of ordinary people. I hear that the Indian Bodhidharma has transmitted the Mind Seal to Ôbai. You should go to him and become his student and make it clear once for all.” The master left, going straightaway to Ôbai, where he formally visited the Fifth Ancestor, Zen Master Daiman. The Ancestor asked him, “Where did you come from?” The master replied, “(I came from) Reinan.” The Fifth Ancestor asked, “What are you seeking?” The master answered, “I only want to become a buddha.” The Fifth Ancestor said,“People from Reinan have no buddha nature. How can you expect to become a buddha?” The master answered, “Concerning people, there are (those from) North or South, but can that be the same with buddha nature?” The Patriarch realized that he was an unusual person and, with a loud voice, howled at him, “You go to the rice-refining shed!” Nô bowed and left.

He went to the rice-hulling quarter, incessantly laboring at the mortar day and night for eight months. The Ancestor, realizing that the time had come for passing on (the Dharma), told the assembly, “The true Dharma is hard to understand. You should not vainly memorize what I say and think that your responsibility is over. (Now) I want each of you to compose a verse according to what you have grasped. If the words match (the truth), I will confer both the robe and the Dharma (upon that person).”

At that time, Jinshû, senior monk among more than seven hundred monks, was a learned man both in Buddhist and non-Buddhist areas and was admired by all people. They all endorsed him, saying, “If not the honorable Shû, who else?” Jinshû overheard people’s praise and, in fact, thought so himself. Having composed his verse, he went several times to the entrance of the master’s room to present it. However, he was extremely nervous and sweated all over. He tried to present the verse but could not. He tried thirteen times in four days to present it but was unable to do so. Then he thought, “It would be better if I wrote it on (the wall of) the hallway. If the master sees it and says it is good, I will come up, show reverence to him and say it is mine. If he says it is unworthy, I will turn around, go into the mountains and spend my years there. What kind of ‘Way’ could I practice, just accepting the venerations of other people?” That night, at the third watch [=around midnight], when no one could notice him, he took a lamp himself and wrote a verse on the wall of the southern hallway, presenting his understanding. The verse read:

The body is the Bodhi tree,

The mind is like a clear mirror upon a stand.

Try to wipe it clean from time to time,

Let no dust stick to it.

( Good practical advice, but demonstrating no deep realization.)

The Ancestor, while walking in kinhin, saw the verse. He recognized it was Jinshû’s verse and praised it, saying, “If later generations practice according to this (principle), they will collect excellent results.” He made everyone learn it by heart and recite it. The master was in the rice-hulling quarter and heard people reciting the verse. He asked a comrade, “What are those phrases?” The comrade said, “Don’t you know? The master is looking for a Dharma successor and had everyone compose a verse about their mind. This is what the senior monk Shû composed. The master extolled it deeply. He will surely pass on the Dharma and transmit the robe (to Shû).” The master asked, “How does the verse go?” The comrade recited it for him. The master, after remaining silent for a while, said, “It’s certainly beautiful, but it’s not yet perfect.” The comrade called out to him, “What does a mediocre man like you know? Don’t talk crazy!” The master said, “Don’t you believe me? Then I will make a verse myself and let it match (the senior monk’s verse).” The comrade did not answer but just looked at him laughing. That night, the master took a young servant boy with him to the hallway. The master held the lamp himself and had the boy write a verse next to Shû’s. It read:

Essentially the Bodhi is not a tree,

Nor does the clear mirror ever sit upon a stand.

Intrinsically there exists not one thing.

Where could any dust stick at all?

(This is a verse about essential reality, essential truth, whether one polishes the mirror or not.)

Seeing the verse, everyone in the temple said, “This is the verse of an incarnated bodhisattva.” People praised it loudly, both inside and outside the temple. The Ancestor knew it was Ronô’s (i.e. Enô’s versel) and said, “Whoever wrote this hasn’t gotten any kensho yet,” (thus attempting to protect Enô from the jealousy and anger of the other monks) and wiped it out. Because of this, the whole assembly did not pay any further attention to it.

When night came, the Ancestor secretly went to the rice-hulling quarter and asked (the master), “Has the rice become white or not?” The master answered, “It has become white, but it hasn’t been sifted yet.” The Ancestor then struck the mortar three times with his stick. The master tossed the rice in the winnow three times and entered the Ancestor‘s room.

_________________________________________________________

PART TWO

The Ancestor said, “Buddhas appear in the world for the sake of the one great Matter. They guide people according to their faculties. Ultimately, such instructions as the “ten stages,” “three vehicles,” and “sudden and gradual (enlightenment)” came into being, to form the teaching of the School. Moreover, (the Buddha) conferred the unsurpassed, extremely subtle, secret and intimate, perfectly clear and true Treasury of the Eye of the True Dharma upon his senior disciple, the Venerable Mahakashyapa. It has been transmitted continuously from ancestor to ancestor, down to Bodhidharma in the twenty-eighth generation. Then he came to this land and found Great Master Ka[=Eka], and it was (eventually) passed on to me. I now pass on the Dharma treasure and the transmitted robe to you. You must guard them well and never allow (the Dharma) to die away.” The master knelt and received the robe and Dharma and said, “I have now received the Dharma, but on whom should I confer the robe?” The Ancestor said, “Long ago, when Bodhidharma first came here, people had no faith in him, so he transmitted the robe to show that one had obtained the Dharma. These days, faith has already matured, yet the robe may instigate people to fight (as we see in the next phase of the story.) So, let it stay with you and do not pass it on. Now you had better go to a distant place and hide there. Wait for the right time, and then teach (and save people). It is said that the life of a person who has received the robe hangs by a thread.”

The master said, “Where should I hide?” The Ancestor said, “Stop when you come to E [=Eshû], hide a while when you reach E [=Shi’e].” After worshipping the feet (of the Fifth Ancestor), the master held the robe high and left.

There was a ferry at the foot of Mt. Ôbai, and the Ancestor personally guided (the master) down there. The master bowed (with his hands on the chest) and said, “Master, please go back. As I have already found the Way, I should cross over by myself.” The Ancestor said, “Although you have already found the Way, I will still have to cross you over.” Thus saying, he took up the pole and crossed over to the other shore. Then, the Ancestor returned alone to the temple. No one in the temple knew what had happened. After that, the Fifth Ancestor no longer entered the hall (to give a teisho). When the assembly came to question him, he said, “My Way is gone.” When asked, “Who has gotten your robe and Dharma?”, the Ancestor answered, “An able one has gotten it.” The assembly discussed this, “The workman Ro’s name is Nô [=able], and when we called on him, he was not there.” Then they realized that he had gotten (the robe and Dharma), and they all started to chase after him.

At that time, there was an (ex-) General of the Fourth Class named Emyô, who had started to aspire for the Way. He was faster than the other (monks) and, in fact, (nearly) overtook the master in the Daiyû Range. The master said (to himself), “This robe represents the faith. How can it be competed for by force?” He placed the robe and bowl on a flat rock and hid in the (nearby) grass. When Emyô arrived and tried to lift them up, he could not do it, no matter how hard he tried. He trembled greatly, saying, “I came for the Dharma, not the robe.” The master appeared at last and sat on the flat rock. Emyô bowed and said, “Please, workman, show me the essentials of the Dharma.” The master said, “Not thinking good or evil: at this very moment, what is the primal face of the senior monk Emyô?”

Upon hearing these words, Emyô was greatly enlightened. Again, he asked, “Besides the secret words and secret meaning you have just revealed to me, is there any other secret meaning yet or not?” The master said, “What I have said to you is not secret. If you reflect (upon yourself), the (so-called) secret is there with (within) yourself.”

Emyô said, “Although I, Emyô, dwell at Ôbai, I have never realized what my true face was. Now, thanks to your instruction, I know it is like a man who drinks water and knows for himself whether it is cold or warm. You are now Emyô’s master.” The master said, “If that is the way you feel, let us both have Ôbai for our master.” Emyô bowed thankfully and returned.

Later, when (Emyô) became a (regular) monk, he changed his name from Emyô to Dômyô, thus avoiding the first character of the master’s name [=Enô]. When someone came to practice with him, he would send that person to practice under the master.

After receiving the robe and Dharma, the master hid himself among hunters in the Prefecture of Shi [=Shi’e].

_______________________________________________________

PART THREE

After ten years, on the eighth day of the first month of the first year of Gihô (676), he moved to the area of South-Sea, where he encountered Dharma Master Inshû, lecturing on the Nirvana Sutra at Hosshô Temple. He lodged under the eaves of the temple hallway.

As a strong wind was flapping the temple flag, he heard two monks arguing, one saying, “The flag is moving,” and the other saying, “The wind is moving.” They argued back and forth but did not match the reality. The master said, “If a lowly man’s arbitrary decision may intervene in your lofty discussion, it is neither the flag nor the wind that is moving; it is your minds that are moving.”

When Inshû heard about these words, he was awe-struck and thought it was quite extraordinary. The next day, he called the master to his room and questioned about the meaning of the flag and wind. The master expounded the principle extensively. Inshû stood up unconsciously, saying, “You are definitely not an ordinary person. Who are you?” The master told him of the circumstances of his Dharma transmission, concealing nothing. There, Inshû made prostrations of becoming a student and asked for the essentials of Zen. Then, he told the four groups (of his own followers: monastic men and women, laymen and laywomen), “I, Inshû, am a completely ordinary man, but now I have met an incarnated bodhisattva.” And he pointed to the layman Ro in the lower row of the group and said, “There he is.” Then he asked that the transmitted robe of faith be shown so that everyone could pay sincere homage to it.

On the fifteenth of the first month, all the well-known figures were called together, so that (the master) could have his head shaved. On the eighth day of the second month, he received the complete precepts from Precept Master Chikô of Hosshô Temple. The platform used for giving the precepts had been established earlier by Tripitaka Master Gunabatsuda(11) in the Sung Dynasty. (If this is not a mistake, it is at least unclear what is meant by the “Sung Dynasty”, as the term commonly refers to the dynasty established in 960 A.D. and lasting until the mid 13th century, hundreds of years after the death of the sixth ancestor. ) He predicted, saying, “Later there will be an incarnated bodhisattva who will receive the precepts on this platform.” Also, near the end of the Ryô Era, Tripitaka Master Shintei(12) planted two bodhi trees with his own hands beside the platform, and he said to the assembly, “A hundred and twenty years from now a greatly enlightened man will appear. He will expound the Supreme Vehicle beneath these trees and save innumerable people.”

After taking the precepts, the master taught the Dharma teaching on the Eastern Mountain beneath those trees, just as the karmic prediction had announced.

The next year, on the eighth day of the second month, the master suddenly said to the assembly, “I do not want to stay here any longer. I need to return to my earlier place.” Therefore, Inshû with more than a thousand monks and lay people saw the master off, who was returning to Hôrin Temple. Ikyo, the governor of the Province of Shô, invited him to turn the Wheel of the subtle Dharma at Daihon Temple, and also received the precepts of formless Mind-ground. (The master’s) disciples planned to record his talks, calling it the “Platform Sutra,” which came to be widely known. Then he returned to (Mt.) Sôkei and showered down the great Dharma rain there. The number of those who got enlightened (under him) was no less than a thousand. At the age of seventy-five, he bathed and died sitting in zazen.

(Keizan’s Teisho)

(At the time of the Dharma transmission, which was like a jar (full of water) emptying itself (into another jar), (the Patriarch) asked, “Has the rice become white yet?” These grains of rice are surely the mysterious and wonderful sprouts of the King of Dharma (Buddha), the liferoots of both saints and ordinary people. Once planted in wild fields, they naturally grow without weeding. Hulled white and completely pure, they do not get sullied at all. Yet, although this is how they are, they are still not yet sifted. If they are thoroughly sifted, then, they pervade inside and outside, they move up and down.

(“Has the rice become white, yet?” Like many of the quotes we find recorded in the annals of Zen, this one has more than one meaning. The more obvious one refers to the state of Enô’s realization: “Has your realization become pure and clear yet?” But the less obvious one is not only more profound, but, I think, also closer to the intended meaning. We should understand it in the context of Enô’s famous gatha:

Essentially the Bodhi is not a tree,

Nor does the clear mirror ever sit upon a stand.

Intrinsically there exists not one thing.

Where could any dust stick at all?

The rice has been white from the very beginning. The word “become” is misleading: how can something “become” what it already is? Nonsense! All Enô has been doing, and all any of us do, is, by way of our Zen practice, to remove the hulls which obscure the original and actual pure whiteness of the rice. Actually I would suggest that the ancestor’s question may be intentionally misleading, as again and again in these stories we see Zen masters setting up trip wires and traps to test their students’ realization. A good, if less than subtle example is this same master’s declaration to the newly arrived Enô that “People in Reinan do not have Buddha Nature.” Enô’s response earns him a spot in the rice-hulling hut.

In this case, when Enô replies, “It has become white but it is not yet sifted”, he is not referring simply to himself. He is talking of the universal and ultimate reality beyond the divisions of self and other. He’s talking of himself, of you, of me: purity from the very beginning in our own lives just as they are: taking out the garbage, washing up after supper, writing a difficult letter to a friend. Just this. Just purity.

But what about this “…not yet sifted”? Surely the sifting – i.e. the perfect and complete separation of the pure white rice from the hulls – or the perfect realization of our fundamental Buddha Nature, untrammelled and unsullied by concept and doctrine, let alone by the all-too-human failings of greed, hatred and ignorance – surely this sifting goes on forever! Not yet sifted? The Buddha himself, it is said, is still working at it. But even as we sift, we realize more and more deeply that in essence there are no hulls; the whole universe is just this pure white rice. Eventually, with sifting “They pervade inside and outside; they move up and down.” Eventually, in absolute oneness, one acts in perfect freedom. Who would that “one” be?)

When the mortar was struck three times, the rice grains were prepared and arranged spontaneously, and the functions of Mind were swiftly displayed.

(Just Tok…Tok…Tok! Who would dare to attempt an “explanation”?

The rice being sifted three times, (Shfftt…Shfftt…Shfftt…) the Wind of the Ancestors (i.e. their spirit), was directly transmitted. (As it had been from the time of the Buddha.) Since then, the night of striking the mortar has not dawned, (i.e. the timeless night, the timeless moment of the transmission has never ended), the day of the endowing hand has not grown dark (the day of the transmission of this wonderful and ultimate gift has not ended; is, in fact, now.)

(This tradition of wordless transmission in Zen goes all the way back to the first transmission of the Dharma, from the Buddha to the second Ancestor, the Venerable Mahakashyapa, who, when the Buddha held up a flower during a gathering on Vulture Peak, smiled his understanding in response. In return, the Buddha announced, “I have the Treasury of the Eye of Truth and Dharma, the wonderful mind of Nirvana. This I entrust to Mahakashyapa.”)

_________________________________

Indeed, the master was a cutter of firewood from Reinan and the workman Ro in the rice-hulling quarter. In old times, he wandered in the mountains chopping with an ax. Even though he had not studied the ancient (Buddhist) teachings and illuminated his mind through them [=kokyô-shhin] in an academic environment, just by hearing one sentence from the sutra the Mind of “dwelling nowhere” emerged.

(To recall, the one sentence was a line from the Diamond Sutra: “Dwelling nowhere, Mind comes forth.”)

This part of the talk is intended to drive home the point that Zen is a Buddhist tradition that does not rely on scripture, that points directly to the fundamental reality of each and every one of us, and gives us the means to access it, realize it, and live it. And so it is emphasized that Enô had no education, no academic training in Buddhist doctrine, and this “ground of no ground” was fertile ground into which this one line from the Diamond Sutra dropped like a seed. The intention is to loosen our attachment to doctrinal ideas, and all other notions and ideas, so that we may free ourselves of them. “If you meet the Buddha on the path, kill him.” Why? Because the Buddha you meet on the path is not yet the real Buddha. Of the real Buddha it may be said that there is no meeting at all, only the realization that no meeting is possible or necessary because at bottom the real Buddha is you (though, as Tozan said, in truth, you are not it.)

Although he had to labor hard with a mortar and a mallet in the rice-hulling room – and although he never practiced Zen, raised questions about the Way or made (Dharma) decisions at the end of the table of studious assembly,

That is, as a labourer in the rice hulling hut, he never practised zazen with the other monks in the Zen hall, never heard teisho, and never was invited to dokusan. He simply hulled rice with mortar and mallet, day after day. That was his practice, as chopping wood had previously been his practice.

by working diligently for eight months, he illumined the mind as a “clear mirror that does not sit upon a stand.”

(A good example for us as we go about our daily routines and chores…)

Enô finishes his gatha with, “Essentially there is nothing at all; On what, then, can the dust collect?” But if there is nothing at all, then there is no mirror, nor is there anything that in an essential way we can consider dust. All gone. But that “all-gone-ness” is the world itself. “Form is no other than emptiness, emptiness no other than form. Form is exactly emptiness, emptiness exactly form.” The world is like a reflection in a mirror in the middle of vast darkness, except that there is no mirror, only reflection.

In the middle of the night, the transmission took place and the lifeblood of successive patriarchs was handed over. Though it did not necessarily depend upon the efforts of many years, it is clear that he completed his realization in all minuteness and thoroughness – once for all. The fulfillment of the Way by all buddhas cannot essentially be measured in terms of long and short time periods. How could you understand the transmission of the Way by the patriarchs through such fixed notions of the past and present?

Here, Keizan is attempting to allay any concerns and blunt any criticism of the Sixth Ancestor for his seeming lack of training and the brevity of his stay with the Fifth Patriarch. Such criticism is certainly understandable. After all, Enô is said to have reached this pinnacle of enlightenment in a matter of a few years, including the period that followed his kensho upon hearing the line from the Diamond Sutra, while the Buddha himself underwent torturous ascetic practices for six years before settling into what would come to be known as the Middle Way. Keizan is presenting Enô as a religious genius at whose level of development the amount and length of training is irrelevant.

Furthermore, in this summer (with the ge-ango),

(i.e. the ninety day summer training period)

I have spoken of this and that for ninety days, criticizing the past and present, and elaborating on the buddhas and patriarchs with rough or gentle words. I have gone into the minute and meticulous details, downgrading to the second and third level, thus besmearing the Zen tradition and exposing the disgrace of our School.

Essentially the Dharma cannot be conveyed in words. But here is Keizan having just spent the last ninety days giving Dharma Talks every day just as if his words actually had some value. Disgraceful! How embarrassing!

Through this, you all may think that you have acquired the principles and gained power, but apparently you have not yet intimately matched the intentions of the patriarchs. Our behavior is not at all like that of our past saints, but because of karmic causes in past lives and abundant luck, we could meet each other like this.

Let’s appreciate this line; it’s for all of us!

If you practice the Way single-mindedly, you are certain to realize it, but many of you have not yet reached the shore (of the other side). You have not yet exactly glimpsed the profound core of the matter. It has been a long time since the saints disappeared, and your work for the Way has not been completed yet. Life does not last forever, so why expect to work on it at a later date? Summer is over, now autumn begins.

It is time for you to be heading for east and west; as usual you have to be scattered here and there. How can you vainly memorize a word or half a phrase and call that my Dharma Way, or resort to a piece of knowledge or a halved understanding and think that you are carrying the load of the Gate of Mahayana? Even if you have sufficiently acquired the power, the shame of our School is still exposed toward outside. How much less could you preach the Way, scattering your illusions and spreading nonsense! If you truly wish to reach this dimension, do not idle away your time day or night or employ your minds and bodies aimlessly.

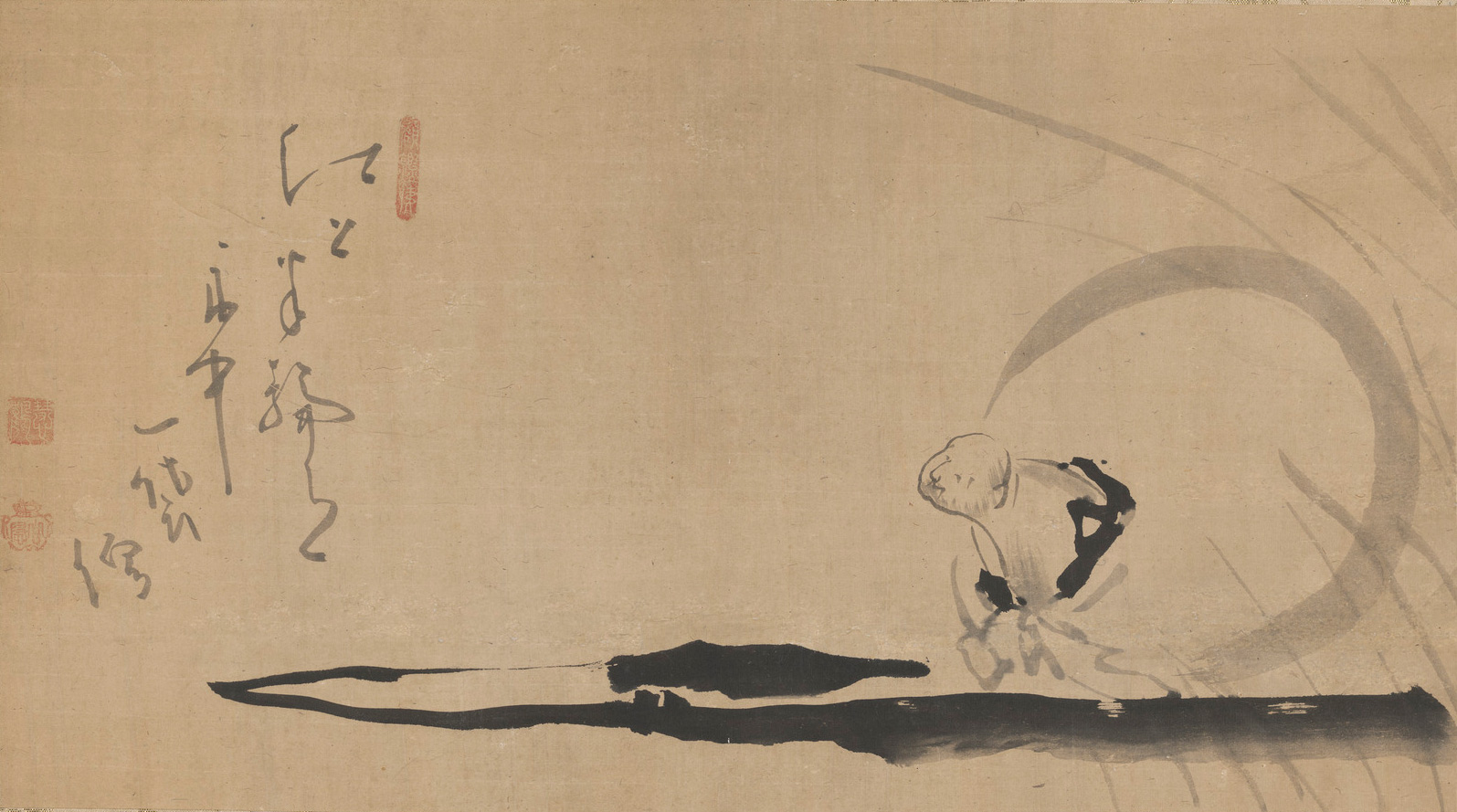

(Verse)

The sound of the mortar is high outside the empty emerald-blue (sky).

The white moon is tossed in the winnow of the clouds – deep and pure is the night.

Such a beautiful verse! I won’t sully it with an explanation.