Teisho on Mu

I’d like to preface this teisho with a brief explanation of one of our rituals, one that you may not be aware of. Traditionally, the monk entrusted with greeting the teacher at the door of the zendo and serving as their aid, bows to them three times. The point of the three bows is that expounding the dharma in words and concepts and images is so difficult that the teacher must be persuaded to attempt it. The teacher declines with the first two bows, and it’s only with the third that they relent and agree to dare to try. I’m very mindful of that tradition and its meaning as I sit down here to deliver this teisho on Joshu’s Dog, first koan in the Mumonkan, first koan for most of us as we begin our Zen journey, and therefore arguably the first koan in importance for most of us.

I’ll begin on relatively safe ground by introducing Mumon himself, the master who compiled the Mumonkan. He lived during the Southern Song Dynasty, roughly the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries CE. This was centuries after what was considered even then to be the golden age of Zen, just prior to and during the Tang Dynasty, that is, the seventh to the tenth century, the age of Hui Neng, Baso, Joshu, Rinzai, Tozan, Tokusan, Unmon and so on – those masters who appear and reappear in most of the classic koans. In 1228, as head monk of the Ryusho monastery in South China, Mumon, as he puts it in his preface, “took up the koans of the ancient teachers and used them as brickbats to batter at the gate, guiding the monks in accord with their various capacities”, and this collection he published as the Mumonkan, the Gateless Barrier, or the Gateless Gate, as it is sometimes called. In this he followed the publication of the Hekiganroku, or the Blue Cliff Record, a hundred years earlier; and followed closely on the heels of the Shoyoroku, or the Book of Equanimity, published just four years before he put the Mumonkan together.

He himself had been given Mu as his koan by his own teacher, and the intensity with which he worked on it is apparent in the instructions that he appends to the koan, and which we’ll come to shortly. After six years, during which he is reported at times to have walked blindly about the monastery knocking his head in desperation on its pillars, he heard the drum announcing the noon meal and came to great enlightenment.

The Song Dynasty was a time of tremendous cultural efflorescence and sophistication, the first in the world to use paper money, to invent gunpowder and the compass, and to have a standing navy, and it was a time of great refinement in all the arts. Koan study became characteristic of Song Dynasty Zen, but this was not an uncontroversial development. It seemed to many that the original radical freedom and profound awakening which the earlier masters embodied could never be attained by studying written stories about them – mere literature! Indeed, Master Daie, the pre-eminent Rinzai master of the time, showed his gratitude to his teacher, Master Setcho, who had compiled the Hekiganroku, by burning the entire collection, including the printing blocks, because he felt that students were too inclined to fall into intellectual interpretations of and discourses about the koans contained in it, rather than being inspired simply to grasp the truth of their own nature directly. When I say “showed his gratitude” I am not being facetious. I am quite sure that the devotion to the Dharma of both these masters would have led Master Daie to believe sincerely that his former teacher would have, or at the very least should have, agreed with him.

The Mumonkan, in contrast with the poetically lofty Hekiganroku and Shoyoroku, was written in a style more direct and down to earth, and featured the fearsomely direct “Mu” as its first koan, and this is probably why it became the primary koan collection, the first one studied, for most, if not all, Rinzai lineages, and for our Sanbozen lineage.

And so… here is the well-known case:

A monk asked Jôshu in all earnestness, “Has a dog the Buddha nature or not?” Jôshu said, “Mu.”

So simple! So direct! Our entire existential dilemma, and its resolution, are summed up in these few words: the monk’s question and Joshu’s answer.

As you look at this koan, please remember that, as in dreams, every character in a koan is you: in this case, the monk, Joshu, and, of course, the dog: all you.

Just as this monk comes to Joshu with his question, so do we come to Zen, to our teachers, to this koan, and to Joshu’s answer, with faith in what the long line of teachers from the Buddha onward have been telling us about our essential nature and the means of realizing it, and with a will to commit ourselves to practice; but on the other hand we come appalled by the world of suffering that we both see around us and experience ourselves, embodied here in the dog, which, of course, is not a pampered pet, but, in Tang period China, a major source of food, and in ancient times a sacrificial animal, dismembered in religious rites. In our own culture we refer to the viciousness and greed of the business world by calling it dog-eat-dog.

The phrase, “in all earnestness”, emphasizes that this is not an academic question, not a question of philosophy or metaphysics. This is an existential question of tremendous personal urgency, for the questioning monk and for you and me. It is literally a matter of life and death.

With apologies for coming on the grammarian, I want to point out how the essential dualism of the monk’s question is expressed clearly in the definite article, the “the”, which introduces the phrase, Buddha Nature — the Buddha Nature — does a dog have the Buddha Nature — giving it a sense of some kind of objective reality, as if it were an identifiable phenomenon among other phenomena. Intellectually we know that’s nonsense, but isn’t that just exactly the nature of our deeply rooted delusion? Buddha Nature as an objective phenomenon, distinct from “I, the subject” who is attempting to look for it!

Some other translations omit the “the” – and give the translation as just, “Does a dog have Buddha Nature?” — but I like this one, by Zenkei Shibayama Roshi, because it emphasizes the dualistic assumptions of the question, of the monk’s point of view — of his essential problem, and of ours. And then the monk follows it with the uncompromising dualism of the “or not” that ends the question. Does it or doesn’t it? Has it or hasn’t it? C’mon Joshu, Yes or no?!

To this challenge, Joshu answers … “Mu”. Literally, “No, it does not.” The monk is perfectly aware that Buddhist doctrine holds that all sentient beings have Buddha Nature — that is his faith, as it is ours — and in all earnestness is trying to understand how that is possible in this world of suffering, embodied in the dog. He knows enough to know that Joshu means something other than, and far more important than, a simple “No, it doesn’t,” and, no doubt, he goes off, as we do, to meditate on what that could be. Some translations of the koan render Mu literally in English as “No”, and in some sanghas students breathe “No” rather than Mu. I’m not sure, but I think the argument for doing so is that understanding the meaning of the word lends force to the practice. In our Sanbozen tradition we feel that this conceptualization is in the end an obstacle, not an aid, as Joshu’s answer, Mu, is beyond all concepts — beyond yes and no, has and hasn’t. It’s significant that on another occasion, asked the same question, he responds, “U”, or “Yes”. Clearly, the literal meaning of the answer is not the point. And so it is thought to be an advantage to non-Chinese and non-Japanese speakers not to be too familiar with the meaning of the word. And even when it comes to that meaning, while it’s true that Mu’s surface meaning is negative, it’s more like a generalized negative. Mu is used in Japanese and Chinese as a prefix, rather like our “un…” or “non…”: unfair, nonconformist, non-Japanese speaker. As such it is more than a specific “No” in answer to a specific question; it’s more like a generalized negative, negating any word or idea that it’s placed in front of. And how appropriate! Absorbed in and by this single syllable, all our dualistic concepts — has, has not, yes, no — are left behind. Even the leaving behind is left behind. Just Muuuuuuuuuu.

It is said in Zen that for enlightenment you need three things: Great Faith, Great Doubt, and Great Determination. This koan is an excellent example of how Zen harnesses the tension between Great Doubt and Great Faith as the force which drives us to realization. Faith says “All Sentient Beings have Buddha Nature”. Doubt says, “What?! Look at that dog there, snarling over food scraps! Look at me, dejected and bitter after being passed over for promotion. That’s Buddha Nature?!” And because this seeming dichotomy is grounded in fundamental, dualistic delusion, we are driven by doubt to get to the very bottom of it, the very bottom of ourselves. In the end, our entire dualistic world is the target of our doubt.

Here’s a quote from Nyogen Senzaki, one of the earliest of Japanese monks to bring Zen to North America:

Each sentient being has buddha nature. This dog must have one. But before you conceptualize about such nonsense, influenced by the idea of the soul in Christianity, Jôshû will say “Mu.” Get out! Then you may think of the idea of “manifestation.” Fine word! So you think of the manifestation of buddha nature as a dog. Before you can express such nonsense, Jôshû will say “Mu.” You are clinging to a ghost of Brahman. Get out! Whatever you say is just the shadow of your conceptual thinking. Whatever you conceive of is a figment of your imagination. Now tell me, has a dog buddha nature or not? Why did Jôshû say “Mu” ?

With Great Faith, Great Doubt, and Great Determination, it is said that it is easier to miss the ground with a stamp of your foot than it is to miss kensho. So … Great Doubt: how do you practise that? Asked to define Great Doubt, Koun Roshi said simply, “Great Doubt is the condition of being one with Mu”.

MUMON’S COMMENT

For the practice of Zen it is imperative that you pass through the barrier set up by the Ancestral Teachers. To attain to marvellous enlightenment it is of the utmost importance that you cut off the mind road, completely extinguishing all the delusive thoughts of the ordinary mind. If you do not pass the barrier of the ancestors, if you do not cut off the mind road, then you are a ghost clinging to bushes and grasses.

What is the barrier of the Ancestral Teachers? It is just this one word “Mu”—the one barrier of our faith. We call it the Gateless Barrier of the Zen tradition. When you pass through this barrier, you will not only interview Jôshu intimately. You will walk hand in hand with all the Ancestral Teachers in the successive generations of our lineage—the hair of your eyebrows entangled with theirs, seeing with the same eyes, hearing with the same ears. Wouldn’t that be wonderfully joyous? Is there anyone who would not want to pass this barrier?

So, then, make your whole body a mass of doubt, and with your three hundred and sixty bones and joints and your eighty-four thousand hair follicles concentrate on this one word “Mu.” Day and night, keep digging into it. Don’t consider it to be nothingness. Don’t think in terms of “has” and “has not.” It is like swallowing a red-hot iron ball. You try to vomit it out, but you can’t.

Gradually you purify yourself, eliminating mistaken knowledge and attitudes you have held from the past. Inside and outside become one. You’re like a mute person who has had a dream—you know it for yourself alone. Suddenly Mu breaks open. The heavens are astonished, the earth is shaken. It is as though you have snatched the great sword of General Kuan. When you meet the Buddha, you kill the Buddha. When you meet Bodhidharma, you kill Bodhidharma. At the very cliff edge of birth-and-death, you find the Great Freedom. In the Six Worlds and the Four Modes of Birth, you enjoy a samādhi of frolic and play.

How, then, should you work with it? Exhaust all your life energy on this one word “Mu.” If you do not falter, then it’s done! A single spark lights your Dharma candle.

For the practice of Zen it is imperative that you pass through the barrier set up by the Ancestral Teachers.

Mumon’s commentary begins with Zen’s essential paradox: we must pass through The Gate that leads to the direct experience of the fact that from the very beginning there is no gate to pass through. We must reach the farther shore to realize that the farther shore is this shore and has been all along. Marvellously, this world, just as it is, is itself Nirvana, vast and void. Hence the title of this collection: The Mumonkan: The Gateless Barrier. The Gateless Gate.

One of Zen’s most powerful appeals in this age of science and doubt, is the Buddha’s deathbed admonition: “Do not believe what I tell you. You must find it out for yourself.” With a genuine kensho, of course, you have indeed found it out for yourself, and need no one’s permission to pass through the gate, but the path of Zen, though direct, is not easy, and the pitfalls along the way include our own creative imaginations, combined with our ego’s many needs and demands, which may lead us to imagine we have come to a realization when we are still clinging to concepts and images. This is why the teacher in Zen, standing there at the gate, is so important. The teacher is there for us as a guide, and the guide is perhaps most important when we need to be told, “Not yet.”

To attain to marvellous enlightenment it is of the utmost importance that you cut off the mind road, completely extinguishing all the delusive thoughts of the ordinary mind. If you do not pass the barrier of the ancestors, if you do not cut off the mind road, then you are a ghost clinging to bushes and grasses.

To cut off the mind road, to completely extinguish all the delusive thoughts of the ordinary mind: this is not a matter of working to shut out delusive thoughts, but rather of just letting them rise and fade, rise and fade, while you remain steadfast with your Mu. In ancient China, ghosts were thought to cling to the bushes and grasses of their former haunts, and so in Zen lore bushes and grasses have come to represent the delusive concepts and images to which we cling, and which stand in the way of seeing clearly our own essential nature, which is the literal meaning of kensho.

What is the barrier of the Ancestral Teachers? It is just this one word “Mu”—the one barrier of our faith. We call it the Gateless Barrier of the Zen tradition.

In the context of this koan, Mu is the barrier; Mu is the challenge; Mu is the means; Mu is the answer; Mu is all these at once, but, most marvellously, most importantly, most essentially, Mu is simply Mu.

That said, more generally and beyond the context of this koan, and of Mumon’s particular lineage, the “one barrier of our faith” is the challenge of our own essential existential question, expressed in different ways by different people. For Mumon, it was this very koan, which is probably why he placed it first among the forty-eight koans of the collection. For Basui, the 14th century Japanese master, it was “Who?” Who is it who is hearing sounds, eating, walking, and understanding? For Dogen it was, if human beings are endowed with Buddha-nature at birth, why did the Buddhas of all ages find it necessary to seek enlightenment and engage in spiritual practice? And it seems that many early masters simply sat with “present moment awareness, focusing on the breath”, as the Buddha put it, in an intense effort to penetrate to essential reality, Buddha Nature, but without formulating their question in words in any definitive way. Mu, in a single syllable, stands for all of these questions, sums them all up, and at the same time gives us the means to an answer, and the answer itself.

When you pass through this barrier, you will not only interview Joshu intimately. You will walk hand in hand with all the Ancestral Teachers in the successive generations of our lineage—the hair of your eyebrows entangled with theirs, seeing with the same eyes, hearing with the same ears. What joy! Wouldn’t that be wonderful! Is there anyone who would not want to pass this barrier?

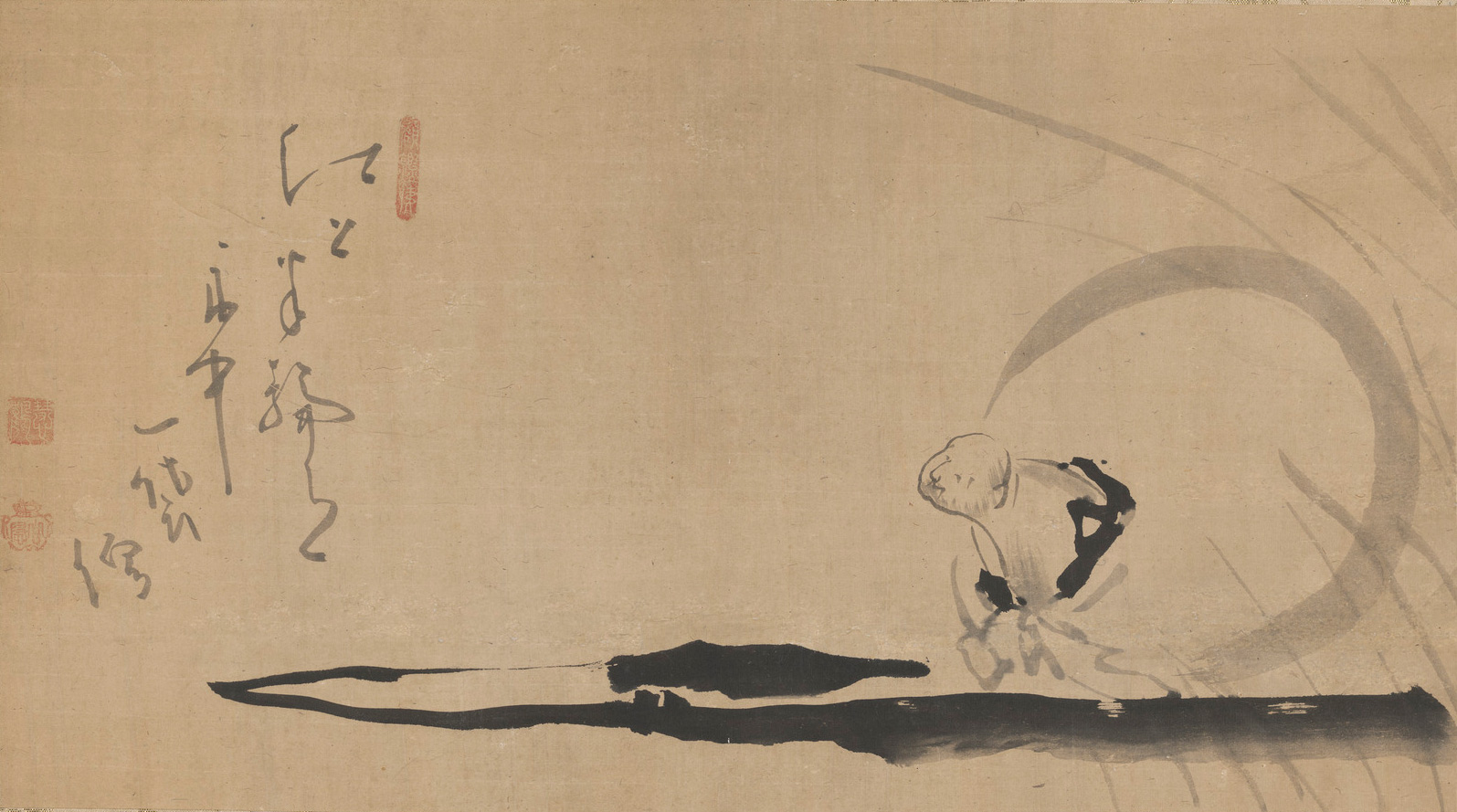

First, a note about eyebrows: in the Zen tradition, eyebrows are symbolic of true understanding, and true teaching. Just google an image of Bodhidharma and you’ll see what I mean. So when Mumon says that your own eyebrows will be entangled with those of the ancient masters, and of the Buddha himself, this is an image of true intimacy. And that you should see with the same eyes and hear with the same ears: the joy at such a moment is beyond all telling!

Mumon sets this wonderful experience as a goal before us, and Joshu gives us Mu as a means of reaching it. “Is there anyone who would not want to pass this barrier?” So it’s quite natural that we should start by coming to Mu as a device. Why are we breathing Mu? To pass through this barrier to our own essential nature; to find enlightenment, peace, and freedom. But we’ve been told again and again – and it is a fundamental article of faith — that in fact there is nothing to gain, that what we awaken to is that from the very beginning, just as we are right at this moment, we are whole, complete, at one in emptiness with the world around us and perfectly free. So in practical terms, what are we to do as we sit down on our cushions and chairs? Here is an instructive dialogue between Nansen and Joshu:

One day Joshu asked Nansen, “What is the Way?”

Nansen said, “Everyday mind is the Way.”

Joshu said, “Does it have a disposition?” (i.e. Should I try to go towards it?)

Nansen said, “If it has the slightest intention, then it is crooked,” (If you try to go towards it you go away from it.)

Joshu said, “If a person has no disposition, then how can they know that it is the Way?”

Nansen said, “The Way is not subject to knowledge. Nor is it subject to no-knowledge. Knowledge is delusive. No-knowledge is just blank consciousness. When the uncontrived Way is really attained, it is like great emptiness, vast and expansive. So how could there be baneful right and wrong?”

At these words, Joshu was awakened.

So we practise Mu because we want to awaken to our essential nature …. And … Mu is not a vehicle to take us somewhere or a device to get us something. There is nowhere to go but we must practise hard to get there. There is nothing to gain, but we must sit with focus and dedication to gain it. On awakening, our lives are just what they were before, and what a wonderful transformation that is! How can this paradox be resolved? Muuuuuu.

So, then, make your whole body a mass of doubt, and with your three hundred and sixty bones and joints and your eighty-four thousand hair follicles concentrate on this one word “Mu.”

Mumon demands that you surrender yourself completely to Mu, making your whole body, your whole being, a single mass of doubt, a single mass of Mu. Sounds terribly intense – hair on fire intense – but just do mu, be faithful to your practice, and it is a natural development.

Some practitioners may feel some degree of anxiety at this stage. This is quite natural, after all, with all that we think of as our “self” apparently on the brink of being lost in the void, but if you are experiencing anxiety in this way, please take it to your teacher in dokusan.

Day and night, keep digging into it.

To the best of your ability hold on to your practice at all times, not just in zazen. Don’t be tempted to talk. Don’t be tempted to check your e-mail. Just Mu. During a retreat, when you have been working on Mu for some time, you will find that it is Mu brushing your teeth, Mu having a cup of coffee, and so on. This will happen naturally if you carry on your practice by simply focusing on the moment at hand. You will discover, too, that just as it is Mu brushing your teeth, the reverse is true as well: just brushing your teeth … that is Mu.

It is like swallowing a red-hot iron ball. You try to vomit it out, but you can’t.

Again, a great image. Vivid and striking. But … I have a couple of cautions regarding it. First, approaches to Mu vary with people, situations, times and conditions. In sesshin, this image of the red-hot iron ball in the pit of your stomach, is a marvellous description of how the practice of Mu is for some people, but it does not fit every practitioner at every moment, even in sesshin, and many practitioners never experience Mu this way, yet arrive at realization just the same. Robert Aitken has spoken of carrying your Mu lightly, and of enjoying your Mu. To practise Mu this way is not to be casual; it’s to be like a well-tuned violin string: taut but not strained. To reach the pitch of intensity that Mumon refers to is not a matter of stretching the string further, or playing the note more loudly; it’s simply a matter of playing that note consistently and faithfully, with focus, courage and determination. As Kubota Roshi used to say, “That is all. That is enough.” Enough, in the end, to swallow up this entire world of delusion.

Again, swallowing a red hot iron ball; tail bone on fire; hair on fire; the mile-high wall of ice; the barrel with the bottom knocked out: Zen language is full of dramatic images. They are useful to a degree, insofar as they point to a reality and challenge us to practise, but can be troublesome when they lodge themselves in the mind as measures of practice or experience, or, worse, as the experience itself. You can’t be doing Mu while you’re checking for red-hot iron balls in your stomach! And if you insist on images such as a barrel with the bottom knocked out as the standard for a kensho experience, you may miss your own experience, dismissing it as unimportant because it does not match your preconceived image. As Mu sweeps away everything else, let it sweep away as well these metaphorical notions of how it should be experienced. Just Mu! And dismiss nothing; take your experiences — no matter how small or transient they may seem — to your teacher.

Don’t consider it to be nothingness. Don’t think in terms of “has” and “has not.”

This is so easy to say, and so difficult to do! Our dualistic concepts of has/has not; self/other; something/nothing; these are so subtle, so fundamental to the way we view the world, that it’s very difficult to uproot them, but over the centuries, from well before Mumon’s time, Mu has served as the breakthrough koan for many thousands of people, the koan by which we manage this uprooting. How do we move beyond this dualistic world? Muuuuuuuuu.

Gradually you purify yourself, eliminating mistaken knowledge and attitudes you have held from the past.

While the kensho awakening is sudden, the lead-up to it is subtle and gradual, and we may be quite unaware of our own progress. But whether we are aware of it or not, the more we practise, the more we intuit the truth of what Buddhas and ancestors have taught; and the thinner become the clouds of delusion, until the moment of sudden breakthrough.

That said, though, I’ll emphasize again the essential paradox of Zen, that every point on the Way is the destination itself. This is an important aspect of what one awakens to in the kensho experience, but even prior to this experience, we are led on by an intuition that this is so.

Inside and outside become one. You’re like a mute person who has had a dream—you know it for yourself alone.

“Inside and outside become one”: a concise description of the condition of samadhi, the precondition for kensho. All divisions break down. As another master put it, “You must see with your ear and hear with your eye”.

Suddenly Mu breaks open. The heavens are astonished, the earth is shaken.

There are many very dramatic accounts of kensho. Yamada Kôun Roshi’s in the Three Pillars of Zen is a good example. These are generally accounts of “daigo-tettei”, or “great enlightenment”, which have come down to us because they are the recorded experiences of major masters, and they are wonderfully inspiring. But don’t be misled. The daigo-tettei experience is generally preceded by at least one, and often numerous smaller kenshos; in Koun Roshi’s case after working his way through the whole koan curriculum. In fact many kenshos are quite quiet, quite gentle. So please discard your expectations based on what others have experienced. Have your own experience. And whatever the experience, however slight you think it, take it to your teacher.

It is as though you have snatched the great sword of General Kuan. When you meet the Buddha, you kill the Buddha. When you meet Bodhidharma, you kill Bodhidharma.

General Kuan was a legendary Chinese general before whose sword no one and nothing could stand. Under the honed edge of Mu delusions fall away, and in kensho the delusion of any separation at all between self and other, you and Buddha, enlightened and ordinary, falls away. This is what it means to kill Buddha, to kill Bodhidharma.

At the very cliff edge of birth-and-death, you find the Great Freedom. In the Six Worlds and the Four Modes of Birth, you enjoy a samādhi of frolic and play.

This is the promise of our Zen practice, the promise of Mu: the Great Freedom, the fundamental Truth of our own being. And where is that cliff-edge? Right here, and right now, of course!

“The six worlds and the four modes of birth” have to do with the Buddhist view of birth and reincarnation inherited from ancient India: the doctrine that in ignorance we are tied to the wheel of birth and death, cycling through earth, and the two realms above it — heaven and the realm of devas — and the three realms below it — animals, hungry ghosts, and hell. Mumon does not say that we find freedom from the cliff edge, or that we somehow escape the six worlds and four modes of birth to find our samadhi of frolic and play. There is no Pure Land other than here. This is it! We are subject inevitably to our own karma, and it is exactly here, wherever we find ourselves, and in whatever circumstances, that we enjoy our samadhi of frolic and play. This is exactly the issue taken up by case number two of the Mumonkan, Hyakujo and the Fox.

As a rather extreme example we find in Buddhist scripture the figure of Devadatta, a cousin of Shakyamuni who was a member of the Buddhist order, but who became a schismatic, condemning others, and Shakyamuni himself, for being insufficiently ascetic. According to legend, after several attempts to have Shakyamuni killed, he was swallowed by the earth and wound up in hell, but such was his power of samadhi, his power of being one with his circumstances, that when in pity Shakyamuni sent a messenger to offer rescue, he declined, saying that he was perfectly happy where he was.

How, then, should you work with it? Exhaust all your life energy on this one word “Mu.” If you do not falter, then it’s done! A single spark lights your Dharma candle.

I don’t think this requires explanation. But I do want to say, how often do we get the chance to do this? How often do we have five days to put everything aside but this one question, the most fundamental and important question of our lives, and to focus solely on it. Don’t pace yourself. Give yourself entirely to your practice, whatever it is.

MUMON’S VERSE

Dog! Buddha nature!

The full presentation of the whole!

A little “has” or “has not”

And body is lost, life is lost!

The verse speaks for itself with crystal clarity: The full presentation of the whole!

I want to leave you with the set of Mumon’s admonitions which serves as a postscript in some editions of the Mumonkan. It’s a post script that warns us, again, that our practice is not a means to an end. You can’t earn kensho with your practice. You can’t earn what you already have, what is your true nature and your essential heritage from the beginning. And don’t wait for it, as if it’s somewhere at the end of the zazen rainbow. Look under your feet.

Listen to Mumon:

To obey the rules and regulations is to tie yourself without a rope. To act freely and without restraint is heresy and deviltry. To be aware of the mind, making it pure and quiet, is the false Zen of quietism. To give free rein to the will and ignore karma is to fall into a deep pit. To abide in absolute awakening, with no darkening, is to wear chains and an iron yoke. To think good and evil is to belong to heaven and hell. To have ideas about the Buddha and the Dharma is to be imprisoned in two iron mountains. To become aware of consciousness at the instant it arises is to toy with the mind. Practising concentration in quiet sitting is the action of devils.

If you try to go forward you stray from the truth. If you retreat you oppose the truth. If you go neither forward nor back you are a corpse with breath. Tell me now what will you do? Make the utmost effort to attain realization in this life! Do not let yourself circulate karma forever.

And Robert Aitken’s comment on these admonitions:

Mumon is like a mad director of traffic. No left turn, no right turn, no U-turn, no advancing, no reversing, no parking. He denies us all options — and this is the best place to be in our practice.