February 17, 2025

THE CASE

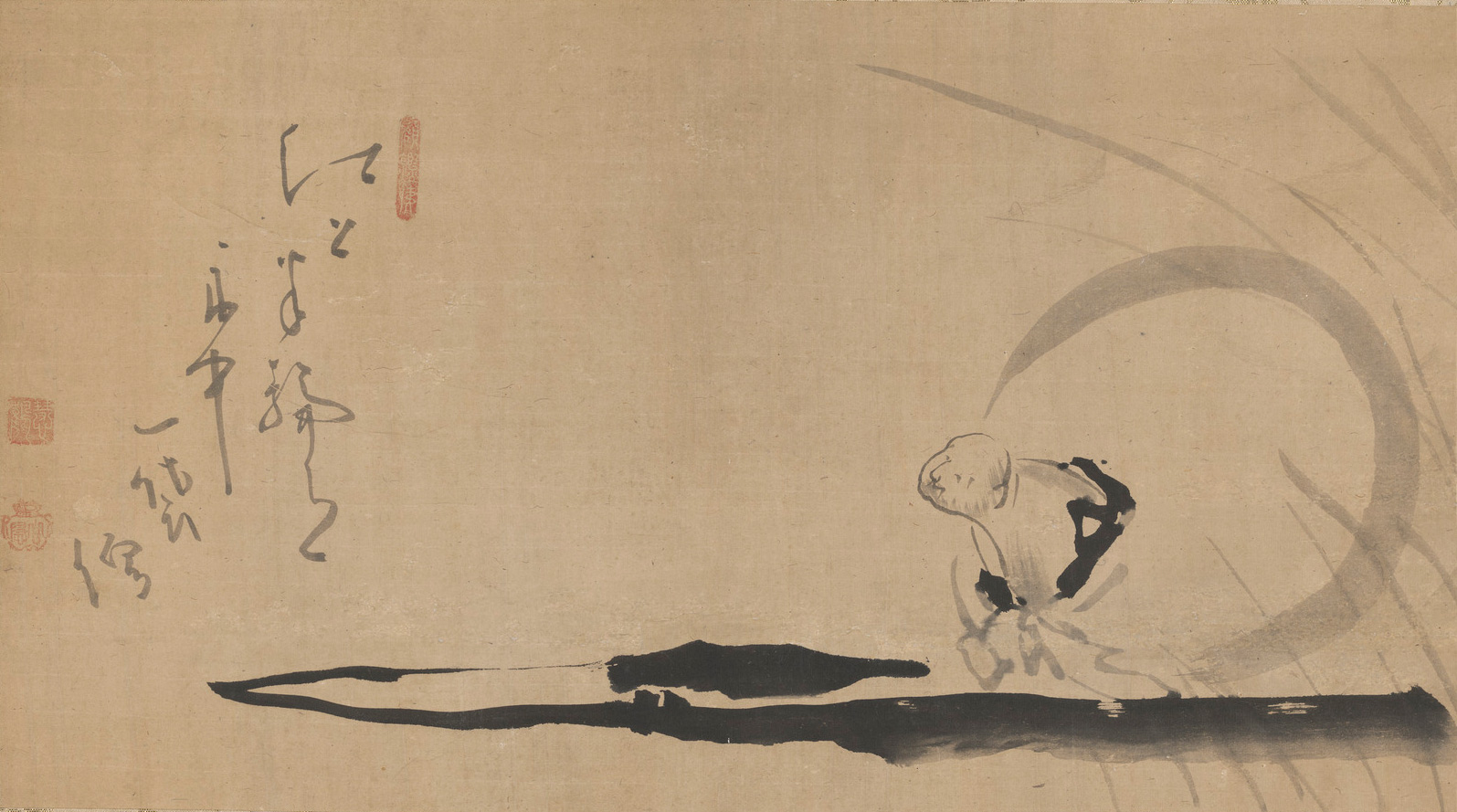

Two monks were arguing about the temple flag waving in the wind. One said, “The flag moves.” The other said, “The wind moves.” They argued back and forth but could not agree.

The Sixth Ancestor said, “Gentlemen! It is not the wind that moves; it is not the flag that moves; it is your mind that moves.” The two monks were struck with awe.

MUMON’S COMMENT

It is not the wind that moves. It is not the flag that moves. It is not the mind that moves. How do you see the Ancestral Teacher here? If you can view this matter intimately, you will find that the two monks received gold when they were buying iron. The Ancestral Teacher could not repress his compassion and overspent himself.

MUMON’S VERSE

Wind, flag, mind move

— all the same fallacy;

only knowing how to open their mouths;

not knowing they had fallen into chatter.

DHARMA TALK

BACKGROUND

The back story of the Sixth Ancestor is told thoroughly in the Dharma Talk, “Denkoroku #33”, which you can find both in this section, and in the “Miscellaneous Talks on Zen Practice” page. Here I will just present a much-abbreviated version of the story.

Daikan Enô was a young, illiterate woodcutter who, enlightened upon hearing a passage from the Diamond Sutra, had come to study with Daiman Konin (Ch. Daman Hongren).

Though only a layman employed in the rice hulling hut, his realization was so profound that, following a gatha competition to see who would succeed Konin, it was he to whom the robe and bowl, symbolizing the succession, were transmitted. On the instructions of Daiman Konin he then fled to southern China to avoid Konin’s monks, who were furious that the succession had gone to someone they considered to be their inferior. There he hid among a band of hunters for ten years.

This is the tale of his reemergence at the temple Hosshoji, where he had come to hear a talk on the Nirvana sutra by Inju, the master of the temple. The story is recorded in “the Platform Sutra”, ostensibly Enô’s account of his own life.

THE CASE

Two monks were arguing about the temple flag waving in the wind. One said, “The flag moves.” The other said, “The wind moves.” They argued back and forth but could not agree.

To be clear: The argument is not about whether this moves and that doesn’t, but about which fact is the primary one. Looked at in terms of primary cause, we find for the wind; looked at in terms of observable fact, we find for the flag. This, then, becomes the argument: Is the observable fact the essential one, or is it the deduced but unobservable cause? This is an important question in the history of scientific inquiry, beginning with the philosophers of ancient Greece. To cite a modern day example of this ongoing argument, behaviourist psychologists will only study and work with observable behaviour, while clinical psychologists work primarily with the unseen mental and emotional causes of the behaviour. When I studied psychology many years ago as an undergrad, the adherents of either side generally did not have much good to say about the other, just like these monks.

Mumon is not impressed:

only knowing how to open their mouths;

not knowing they had fallen into chatter.

Assuming that by this vague, “they”, Mumon is referring to the two monks, the criticism is straightforward and clear. Having come to the monastery to address “The Great Matter” they’ve taken their eye off the ball and fallen into philosophy. Enô brings them back to the essential issue: What is this? What is our essential reality? This is not a philosophical question. It’s a quest to resolve experientially in our own being the fundamental questions of life, death, and suffering.

The Sixth Ancestor said, “Gentlemen! It is not the wind that moves; it is not the flag that moves; it is your mind that moves.”

And here Mumon says,

If you can view this matter intimately, you will find that the two monks received gold when they were buying iron.

This is self-explanatory I think. And the little story ends with, “The two monks were struck with awe. “ In fact, according to another source, they rush inside to tell their master that an extraordinary individual stands at the gate, and they tell him of their exchange with him. Immediately the master suspects that this may well be the famous Sixth Ancestor, who it is rumoured has been living in hiding in the area. He invites him in, finds his suspicion confirmed, and shortly afterwards Enô is ordained and begins his teaching career.

Back to the case: On hearing that it’s really the mind that is moving we say, along with the monks, no doubt, “Ahhhh! Of course! Yes, the whole universe unfolds in this very mind! Of course!”

But then, in his comment, Mumon takes it a step further:

“It is not the wind that moves. It is not the flag that moves. It is not the mind that moves. How do you see the Ancestral Teacher here?”

So ruthless, that Mumon. Just when we think we’ve got it, he kicks the conceptual props out from underneath us. Not the flag not the wind not the mind. Well what in the world are we left with? The unnameable, inexpressible, ungraspable and inconceivable “it” which lies unobtrusively between the lines of so many koans. Like the “it” of “It’s raining”.

Sorry, Mumon says, you’re still conceptualizing your way through this question of what is moving. If you dig your way down into this mind that is moving, you will find that essentially there is no movement at all.

As Mumon says in the first two lines of the verse,

Wind, flag, mind move — all the same fallacy;

Essentially there is nothing at all. Perfect stillness in perfect emptiness, and in this the perfect unity of all that is. This realization of “nothing-at-all”, perfect emptiness, is kensho. In our lineage we are aiming for this kensho with our first koan, Joshu’s Dog: Mu. And we are aiming to broaden and deepen realization in these subsequent koans. And yes, I say “aiming”, implying means and a goal, which is perfectly fine, not to mention obvious, as long as we remember the other side of the coin: no means and no goal, nowhere to go and nothing to gain, just this moment, just this Mu. In a recent reading we heard Rinzai tell us that so long as we are “doing something” we are not really practising. That’s the essential side of the coin. The coin has two sides, and it’s just one coin.

Now of course, if you come to Mumon and announce that there is no movement at all – perfect stillness – you shouldn’t be surprised if his response is whack whack whack! You’re still dealing with concepts: words and phrases. This empty stillness is you yourself, so somehow you have to present yourself as this empty stillness, or this empty stillness as yourself, and you have to do it in the context of this particular koan, the wind and the flag.

These presentations in the dokusan room are a form of communication. What is being communicated is beyond the power of words to frame, beyond our our powers of conception to grasp. “It” is literally inconceivable. It’s not that in making these presentations we never use words; it’s that we freely use whatever is appropriate: words, gesture, movement. I remember a theatrical director who demanded that actors auditioning for a part in his play portray bacon frying in a pan. If that were an appropriate response to a koan, that’s what you would do. Here you have to present yourself as the essential empty stillness of the flag moving in the wind. And to do that, you have to experience that stillness, empty and vast, as yourself.

So back to this koan. The basic tension in every koan is the tension between essential and phenomenal, or between absolute and conditional. That is the tension, the dichotomy, that we must resolve, and it is presented to us here as a flag waving in the wind. Right there is the whole moving world, and at the same time the world perfectly still. It’s being able to realize no-movement and live it as movement in a moving world that is the freedom of enlightenment. Ultimately, this koan asks that we demonstrate that for Mumon, using this flag in the wind.

That said, what does the last line of the comment mean:

The Ancestral Teacher could not repress his compassion and overspent himself.

“Could not repress his compassion”: that’s clear enough. He earnestly wishes to set the monks on the path, to “open the Way” to them. But what about “(he) overspent himself”? Does Mumon dare to offer a criticism of the Sixth Ancestor, arguably a figure equal in importance to Bodhidharma? In fact I believe he does. And what is the criticism? It is that in his compassion for the two monks, he himself has fallen into conceptualizing. It’s the mind that moves? Nonsense! Just another concept!

That said, I would say that Mumon understands perfectly well that Enô is employing what the Buddha called, “skillful means”. That is, Enô is encouraging the two monks to take the next step on the path. Even though what he says may be criticised as conceptual, it points the monks in the right direction. Skillful means are simply the means employed to draw the monks, and us, onward, step after step.

So, though the criticism is real enough, its function is to alert us to the trap of conceptualizing the moving mind, rather than to point up flaws in the Sixth Ancestor.

Here is another example of skillful means:

The great master Baso, teacher of Nansen and Hyakujô, grandfather in the Dharma to Jôshu and Ôbaku, was famous for teaching that “Ordinary mind is Buddha”. A monk asked him, “Why do you say that mind is Buddha?” His answer was, “To stop babies from crying.” Babies! In other words, those not yet far along on the path, by which he means the thousand or so monks in his monastery. A few years later, when asked “What is Buddha?” he answered, “No mind, no Buddha.” Step by step by skillful means.

In Zen imagery, grasses and weeds represent the delusory phenomenal world, the world of concepts, of words and phrases, but often it’s in the weeds of words and phrases that one teaches. That’s where Baso is teaching, and where in this koan Enô is teaching, though they are both pointing to a reality beyond the weeds, a reality that they are encouraging us to see and to live in our daily life.

I’ll conclude with some lines from T.S. Eliot’s Burnt Norton:

…at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement. And do not call it fixity,

Where past and future are gathered.

Neither movement from nor towards,

Neither ascent nor decline. Except for the point, the still point,

There would be no dance, and there is only the dance.