The Case

Tokusan (Ch. Deshan) visited Ryûtan and questioned him sincerely far into the night. It grew late and Ryûtan said, “Why don’t you retire?” Tokusan made his bows and lifted the blinds to withdraw, but was met by darkness. Turning back he said, “It is pitch dark outside.”

Ryûtan lit a paper candle and handed it to Tokusan. Tokusan was about to take it when Ryûtan blew it out. At this, Tokusan had sudden realization and made bows. Ryûtan said, “What truth did you discern?” Tokusan said, “From now on I will not doubt the words of an old priest who is renowned everywhere under the sun.”

The next day Ryûtan took the high seat before his assembly and said, “I see a brave fellow among you monks. His fangs are like a sword-tree. His mouth is like a blood-bowl. Give him a blow and he won’t turn his head. Someday he will climb the highest peak and establish our Way there.”

Tokusan brought his notes on the Diamond Sutra before the Dharma Hall and held up a torch, saying, “Even though you have exhausted the abstruse doctrines, it is like placing a hair in vast space. Even though you have learned all the secrets of the world, it is like letting a single drop of water fall into an enormous valley.” And he burned up all his notes. Then, making his bows, he took leave of his teacher.

Mumon’s Comment

Before Tokusan crossed the barrier from his native province, his mind burned and his mouth sputtered. Full of arrogance, he went south to exterminate the doctrine of a special transmission outside the sutras. When he reached the road to Reishu, he sought to buy refreshments from an old woman. The old woman said, “Your Reverence, what sort of literature do you have there in your cart?” Tokusan said, “Notes and commentaries on the Diamond Sutra.” The old woman said, “I hear the Diamond Sutra says, ‘Past mind cannot be grasped, present mind cannot be grasped, future mind cannot be grasped.’ Which mind does Your Reverence intend to refresh?”

Tokusan was dumbfounded and unable to answer. He did not expire completely under her words, however, but asked, “Is there a teacher of Zen Buddhism in this neighborhood?” The old woman said, “The priest Ryûtan is just up the road.” Arriving at Ryûtan’s place, Tokusan was utterly defeated. His earlier words certainly did not match his later ones.

Ryûtan disgraced himself in his compassion for his son. Finding a bit of a live coal in the other, he took up muddy water and drenched him, destroying everything at once. Viewing the matter dispassionately, you can see it was all a farce.

Verse

Seeing the face is better than hearing the name;

hearing the name is better than seeing the face.

He saved his nose,

but alas he lost his eyes.

Adapted from Aitken, Robert. The Gateless Barrier (pp. 210-211). Kindle Edition.

(Substitutions of Japanese names for Chinese are mine.)

DHARMA TALK

This is a favourite koan of mine, and, I suspect, of many. Tokusan is such an interesting character, and the story is so dramatic, presenting both Tokusan and us with challenging questions, that it’s a memorable stand-out in the koan collections.

As the back story revealed in Mumon’s comment is an important part of the overall story, I think it would be helpful to reverse the ordinary order of things and deal with the comment first.

Mumon’s Comment

Before Tokusan crossed the barrier from his native province, his mind burned and his mouth sputtered. Full of arrogance, he went south to exterminate the doctrine of a special transmission outside the sutras.

Tokusan at this time, the height of the Tang Dynasty and the golden age of classical Zen, was still a relatively young man in his thirties, but already a renowned scholar of the Diamond Sutra, and frequently invited to speak on it. He was well-known for trundling his weighty commentaries in a wheelbarrow as he went from speaking engagement to speaking engagement.

Hearing of the Zen sect to the south, and their blasphemous assertion that rather than wait and pray, kalpa after kalpa, for Buddhahood, one could actually attain it in this life simply by turning inwards and seeing directly into one’s own mind, he was so outraged that he set out to exterminate this pernicious doctrine. As this was a journey of about 1,000 km., either his outrage must have been extreme, or perhaps there was something else going on. More on that later.

When he reached the road to Reishu, he sought to buy refreshments from an old woman. The old woman said, “Your Reverence, what sort of literature do you have there in your cart?” Tokusan said, “Notes and commentaries on the Diamond Sutra.” The old woman said, “I hear the Diamond Sutra says, ‘Past mind cannot be grasped, present mind cannot be grasped, future mind cannot be grasped.’ Which mind does Your Reverence intend to refresh?”

And so we find him on the road, approaching Reishu in South China, home of many Zen temples. Pausing for some refreshment, he has his first encounter with a true master of the Southern School, an old woman selling tenjin, a kind of dim sum, from a roadside stand. She is nameless, but her question to Tokusan is worthy of any master. She first asks him what he’s carrying in his barrow, to which he proudly replies, “My commentaries on the Diamond Sutra”. We don’t find it in Mumon’s version of this koan, but the story recorded elsewhere goes on to say that she responds with a little game. She tells him that if he can answer her question she will treat him to the tenjin, but if not she won’t even sell it to him, and he’ll have to go elsewhere.

In the story as it is translated above, the old woman asks simply, “Which mind does your reverence intend to refresh?” But in fact, there is some clever wordplay employed here by the old woman that this general translation misses. The characters for “tenjin” have been translated in a variety of ways. The literal meaning of the two characters is “dot” and “mind”. “Dot” has been interpreted and translated as “Punctuate”, and also as “point”, so then tenjin could mean “punctuate the mind”, “pointing to the mind”, or “one-pointed mind”.

I prefer “pointing to the mind”, as her question then becomes,

To which mind will the Tenjin point?

However we translate it, Tokusan is stopped cold, absolutely flumoxed. He has nothing to say. The old woman demands that Tokusan, the king of the Diamond Sutra, step away from his wheelbarrow of commentaries, his carefully built palace of abstractions, and engage genuinely – intimately – with this moment, here and now. He’s hungry, he’s tired, he can smell the tenjin, and the old woman is looking at him with a wry smile — and he can’t do it. His wheelbarrow full of commentaries, and his head full of ideas and concepts and images and doctrines are of no help at all.

Tokusan was dumbfounded and unable to answer. He did not expire completely under her words, however, but asked, “Is there a teacher of Zen Buddhism in this neighborhood?” The old woman said, “The priest Ryûtan is just up the road.”

And here Tokusan begins to show what he’s made of. More specifically he begins to show something of the underlying motivation that brought him all this way. Instead of countering with defensive bluster, he recognizes that here is a person who knows something he doesn’t know, offering a challenge that he is clearly not equal to, and with humility he opens up and asks respectfully to be directed to the woman’s teacher.

Now, just a brief note on these roadside women: we encounter them in a number of koans. They are always nameless, in accordance with their social status as peasant women, but they are clearly masters. If they had been men, they would have had a monastery on a mountain and a name to go with it.

Arriving at Ryûtan’s place, Tokusan was utterly defeated. His earlier words certainly did not match his later ones.

Comparing his words of arrogance as he departs for the South, and his words of humility when he asks to be directed to the local Zen teacher.

The old woman tells him that there is a teacher, presumably her own, just up the road — Ryûtan — and Tokusan sets off.

Mumon doesn’t mention it, but another version of the story tells us that by the time he arrives he has recovered a little of his self possession, and he greets Ryûtan with something clever of his own.

Ryu means “dragon”, and “tan” means “marsh”. Dragon Marsh was the name of the temple, and of its location, and was the name which the master of the temple had taken for himself, after the custom of the time.

The dragon in Asia is a symbol of spiritual power, so Dragon Marsh, the terminus of Tokusan’s pilgrimage, can be seen as the great goal of enlightenment.

So on entering the Dharma Hall, he greets Ryûtan with, “Long have I heard of Ryûtan, but on arriving I see neither marsh nor dragon”, but Ryûtan responds, “You, yourself, have seen Dragon Marsh in person.”

Tokusan has made a declaration from a philosophical standpoint of emptiness — neither dragon nor marsh — and Ryûtan responds, like the old woman, by throwing him back on his own experience of this very moment: Now you see Ryûtan in person! Look! Look! This is it! Just this! And once again Tokusan is silent.

And this is the point at which we enter the koan.

THE CASE

Tokusan visited Ryûtan and questioned him sincerely far into the night. It grew late and Ryûtan said, “Why don’t you retire?” Tokusan made his bows and lifted the blinds to withdraw, but was met by darkness. Turning back he said, “It is pitch dark outside.”

Recognizing that Ryûtan is truly a a great master, keeper of a great treasure, Tokusan begins to, as Mumon puts it, “sincerely” question him, abandoning his pride of accomplishment in his fame as a scholar and opening himself to Ryûtan’s instruction.

Mumon tells us that he has come south full of arrogance, determined to show those Zen monks the error of their ways, but let’s give Tokusan his due. You don’t devote your entire life to a text which purports to contain the key to the fundamental nature of reality if you have only a passing interest in it. I must say, it seems to me that under all that scholarship, and even under the arrogance, there is a genuine, burning desire to get at the truth, and a fundamental, if as yet unacknowledged, dissatisfaction with his own intellectual approach to “The Great Matter”. He is thrown back on his heels first by the old woman, and then by Ryûtan, with his “Now you yourself have seen Dragon Marsh”. This, after all, is why he came all this way! The crack opens, and begins to widen.

The koan proper begins with “Tokusan visited Ryûtan and questioned him sincerely far into the night.“ This is very succinct, but understand that the word “visit” means more than just dropping in – after all, he has travelled a thousand kilometers on foot, pushing a wheelbarrow, for this “visit”. And “questioned him sincerely far into the night” refers to night after night of intense questioning. To use the word, “sincere”, is to say that Tokusan had become genuinely open and ready.

The main theme of the Diamond Sutra, which Tokusan had spent his adult life analyzing and writing commentaries upon, is the fundamentally illusory and empty nature of reality – Buddha nature, to give it a name, or “not-a-thing-ness” as Ryôun Roshi calls it. It is the sutra on hearing which Hui Neng, the sixth ancestor, came to instant enlightenment, and after which he posted his famous poem on emptiness, which ends, “Fundamentally there is not a single thing; on what could dust alight?”. The Diamond Sutra was revered in its own time as one of the most important of all Buddhist sutras, and indeed a copy of it is the oldest printed book in the world. It is, no doubt, this sutra that was the basis for Tokusan and Ryûtan’s talking far into the night.

Tokusan made his bows and lifted the blinds to withdraw, but was met by darkness. Turning back he said, “It’s pitch black outside.”

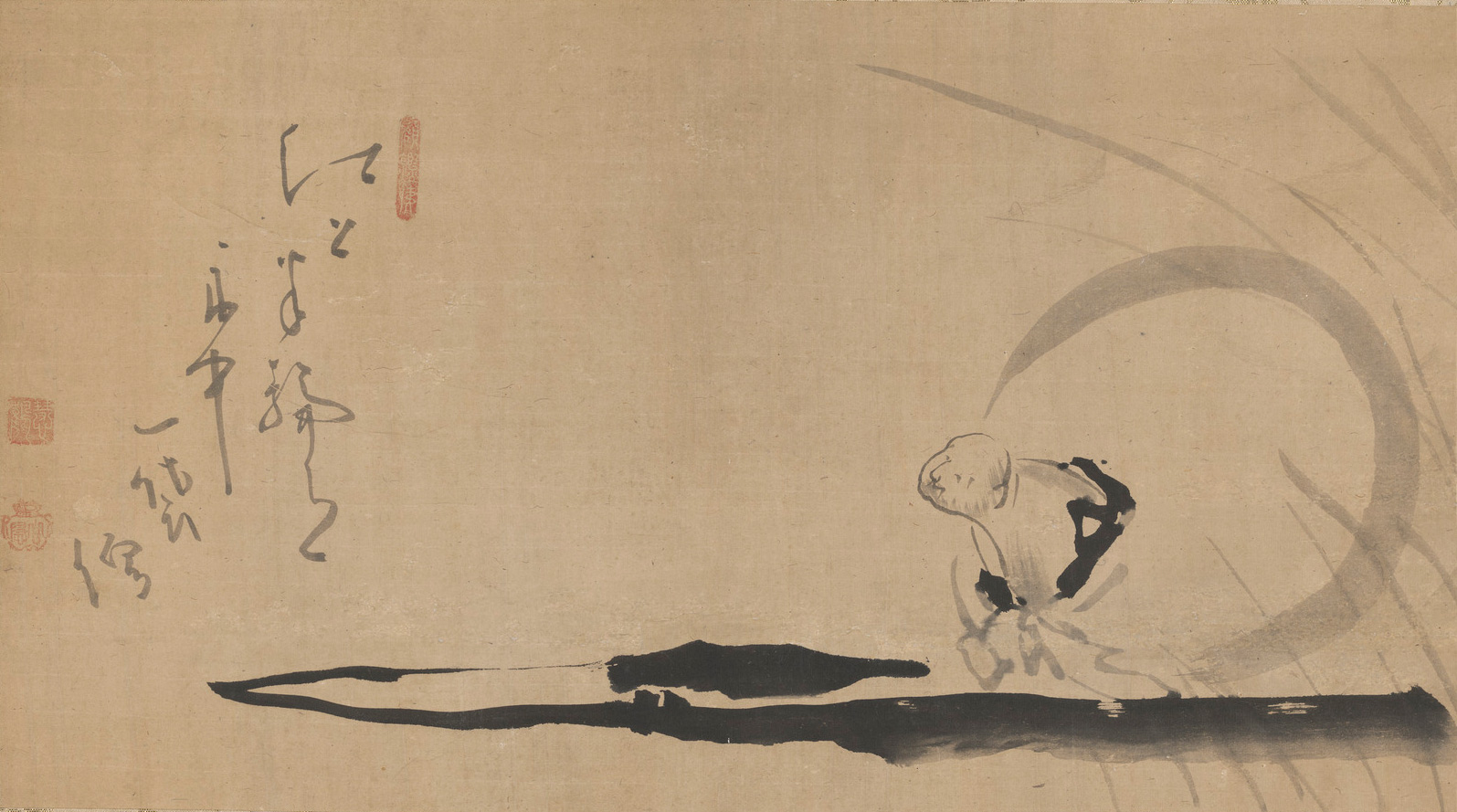

Ryûtan lit a paper candle and handed it to Tokusan. Tokusan was about to take it when Ryûtan blew it out. At this, Tokusan had sudden realization and made bows.

So here is the meat of the koan. Of all the senses which one is most closely connected to reason and conceptual thinking? Surely it is sight. Apollo is not only the god of the sun, by whose light we see, but the god of reason as well, and is often set in opposition to Dionysus, the god of passion and wine, which cloud our rational mind. We depend on the light of reason for our conceptual understanding of the world. Tokusan is right on the edge of realization; while still clinging to philosophy and doctrine, he is ready to let go, when Ryûtan suddenly gives him a push. He blows out the candle, and for Tokusan, in the shock of his sudden blindness, everything falls away: his life, his scholarship, his pride, his ego, all those commentaries, his entire world. What is he left with?

If sight is our main medium for grasping the world in a dualistic way, we may say that “inner vision”, the vision of the “third eye” in Asian cultures, is our medium for grasping the essential world, the world of Buddha Nature. In fact in Zen our apprehension of this essential world is usually referred to as a kind of seeing, rather than a kind of knowing. The prophet who is outwardly blind, but has inward vision, is common to many cultures. A classic western example is Tiresias, the blind prophet of Thebes, who appears in the Odyssey and in a number of other works of Greek literature. Then there is Gloucester in King Lear; there is the Johnny Depp character, William Blake, in Dead Man; and perhaps most famous of all, the Christian apostle Paul, who is struck blind on his way to Damascus. All of these are examples of men who gain inner vision when they lose their sense of sight.

Ryûtan, sensing that Tokusan is on the brink of realization, sees and seizes his opportunity and shocks him with sudden blindness. And for his part, Tokusan, after nights of questioning the master, searching for Truth in the master’s words, finds himself thrown back entirely onto himself, his own fundamental being.

Tokusan had sudden realization and made bows. Ryûtan said, “What truth did you discern?” Tokusan said, “From now on I will not doubt the words of an old priest who is renowned everywhere under the sun.”

Tokusan does not answer the question directly. After all, how could he answer in words about a realization beyond words. Instead he says, “From now on I will not doubt the words of an old priest who is renowned everywhere under the sun.”

We are not told Ryûtan’s on-the-spot reaction to this declaration by Tokusan, though it seems from his statement to the assembly the next morning that he has approved it. Tokusan’s words say little about his realization, but it’s clear to Ryûtan from Tokusan’s manner that he has indeed had a great kensho. It’s generally assumed, as you can see from the title of this koan, that “the old priest renowned everywhere under the sun”, that Tokusan refers to, is Ryûtan, but it could as well be the Buddha himself. Ultimately it doesn’t matter; they are rolling the same Dharma Wheel. Ultimately, they are the same.

The next day Ryûtan took the high seat before his assembly and said, “I see a brave fellow among you monks. His fangs are like a sword-tree. His mouth is like a blood-bowl. Give him a blow and he won’t turn his head. Someday he will climb the highest peak and establish our Way there.”

“A brave fellow…. Give him a blow and he won’t turn his head.” From the Heart Sutra: “The Bodhisattvah lives by prajna paramita, with no hindrance in the mind, no hindrance, and therefore no fear”. This is the foundation, flowing and perfectly still, of “Give him a blow and he won’t turn his head.”

“Fangs like a sword tree”, “Mouth like a blood bowl”. Zen is often given to various kinds of violent imagery, but Ryûtan’s imagery is extreme, perhaps because he is now familiar with Tokusan’s character and has a sense of his future teaching style:

“Speak and you get 30 blows! Don’t speak and you still get 30 blows!”

Or

Tokusan said to the monks, “As soon as you ask, you have erred. If you don’t ask you’re also wrong.”

A monk came forward and bowed. Tokusan struck him.

The monk said, “I just bowed. Why did you hit me?”

Tokusan said, “What use would it be to wait until you opened your mouth?”

His severity came forth as well in his talks:

Tokusan entered the hall and addressed the monks, saying: I don’t hold to some view about the ancestors. Here there are no ancestors and no buddhas. Bodhidharma is an old, stinking foreigner. Shakyamuni is a dried piece of excrement. Manjushri and Samantabhadra are dung carriers. What is known as “realizing the mystery” is nothing but breaking through to grab an ordinary person’s life.

Tokusan is the living embodiment of “If you meet the Buddha on the path, kill him.”

Last Paragraph of Commentary.

Ryûtan disgraced himself in his compassion for his son.

Night after night, talk talk talk!

Finding a bit of a live coal in the other, he took up muddy water and drenched him, destroying everything at once.

He blew out the candle!

Viewing the matter dispassionately, you can see it was all a farce.

Of course — just an elaborate show, for whose benefit?

Denoument

Tokusan brought his notes on the Diamond Sutra before the Dharma Hall and held up a torch, saying, “Even though you have exhausted the abstruse doctrines, it is like placing a hair in vast space. Even though you have learned all the secrets of the world, it is like letting a single drop of water fall into an enormous canyon.” And he burned up all his notes.

This passage pretty much speaks for itself. An intellectual understanding of the Dharma is ludicrously inadequate as the basis of a genuinely spiritual life, a genuine Life, and in fact can be a serious obstacle to realization.

Even so, consider what it would have meant to the devoutly earnest monks of Ryûtan’s monastery, and to subsequent generations of Buddhist monks, when Tokusan burns his life’s work, these widely known commentaries on this supremely important sutra, upon experiencing enlightenment. Absolutely shocking; absolutely radical!

“If you meet the Buddha on the path, kill him.”

For Tokusan it was essential that he burn his notes and move on. In Tokusan’s case, in burning his notes he was burning, too, his own prideful attachment to them. That was something he needed to do.

But it’s not always so. To each according to his needs. There are examples of Zen masters who were well-versed in Buddhist scripture and in the Chinese classics, and made use of them in their teaching. And there are those, like Tokusan, who must radically reject them. As for students, they go where their affinity takes them. In fact in Zen, affinity is another word for karma.

Tokusan went on to become famous for his physically rigorous teaching methods — few words and lots of blows — but though from our 21st century, western viewpoint we might question such teaching, the fact is that it must have been brilliant, as his disciples and descendants included some of the most famous and important masters of their generation, and indeed one master, Unmon, who some consider to have been the greatest of all Zen masters.

Verse

Seeing the face is better than hearing the name;

hearing the name is better than seeing the face.

He saved his nose,

but alas he lost his eyes.

I will just say that the first two lines can be taken in two ways. First, of course, they refer to the meeting between Tokusan and Ryûtan. It’s Ryûtan’s face that Tokusan is seeing after hearing his name. So … seeing the reality is better than just hearing about it. But what about the opposite? Hearing about the reality is better than seeing it. The first is obvious, the second, not so much. Consider though that Ryûtan is presented in this koan as a renowned priest, very famous, but when Tokusan sees him, there is neither dragon nor marsh, just a fellow on a cushion.

Secondly, seeing the face refers to seeing the primal face, your face before your parents were born. Seeing it, of course, is far better than just hearing about it. But on the other hand, hearing about it we think of it in very grand terms, but when we encounter it, it turns out to be everyday reality: a cup of coffee on a table, a dog gambolling on a beach. Nothing special, and yet marvellous!

He saved his nose.

When an Asian wishes to indicate him or herself, they do not point to their chest, as Westerners do, but to their nose: he saved himself.

but alas he lost his eyes.

But he found his Eye!