THE CASE

A monk said to Jôshu, “I have just entered this monastery. Please give me instruction.” Jôshu said, “Have you eaten your rice gruel?” The monk said, “Yes, I have.” Jôshu said, “Wash your bowl.” The monk had an insight.

MUMON’S COMMENT

Jôshu opened his mouth and showed his gallbladder, heart, and liver. On hearing it, I hope the monk truly got it. I hope he did not mistake the bell for a jar.

MUMON’S VERSE

Because it’s so very clear,

it takes a long time to realize.

Just know that flame is fire,

and you’ll find your rice has long been cooked.

DHARMA TALK

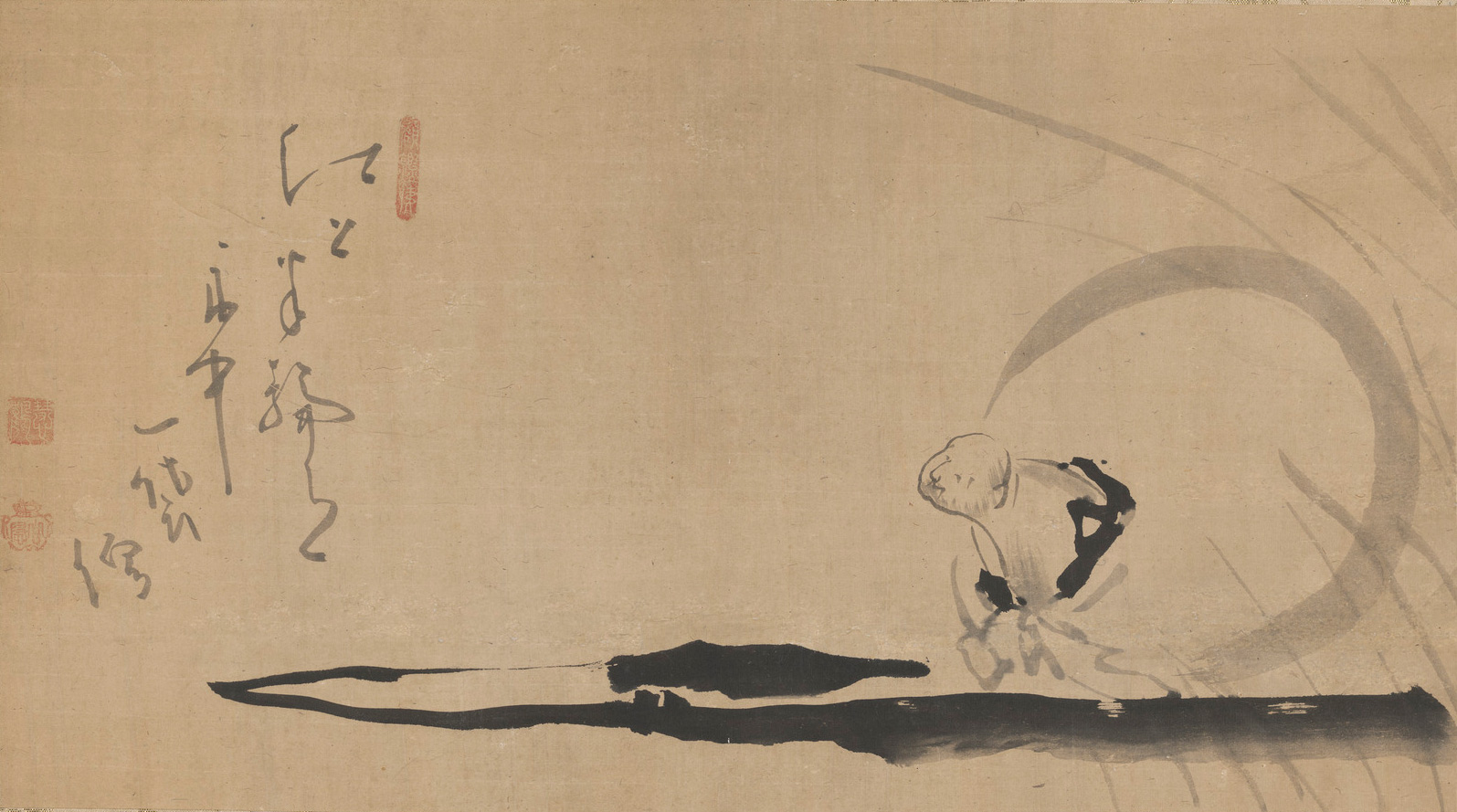

Once again we meet Jôshu, who appears 7 times in the Mumonkan, beginning with Case #1, his “Mu”; and many more times in the Blue Cliff Record and the Book of Equanimity. This koan is a perfect example of his “lips and mouth” Zen. Legend has it that when he spoke, one could see light playing about his mouth.

A monk said to Jôshu …

The monk is nameless; therefore we can assume that he is a monk of no notable accomplishment: just a monk. This does not mean he has no “eye”; just that he did not go on to be the sort of major master who gets his name recorded in koans.

“I have just entered this monastery….”

We can assume he has been there at least a day, perhaps more.

“….Please give me instruction.”

In this koan it helps, I think, to know a bit about Jôshu, enabling us in turn to deduce a bit about the monk.

Jôshu was part of the 4th generation of Zen masters after Enô, the 6th ancestor, and part of the 2nd generation after Baso, the great master who had more than 70 dharma successors. Jôshu at the time of this koan was one of the greatest masters of that age, the Tang Dynasty, or in fact of any age. Dogen Zenji called him, “the Old Buddha”.

This does not mean that he had crowds of disciples. His Zen may have been “lips and mouth”, rather than fists and shouts, but that does not mean life was easy in his monastery. Rather, it was a pretty ascetic existence, and it was no doubt for that reason he apparently had only a small number of monks with him at any one time.

So this is the master that this monk has chosen to study with. He knows what he’s getting into. He wouldn’t be there if Jôshu weren’t the great master that he is, and he wouldn’t be prepared to endure the harsh conditions at Jôshu’s monastery if he were not somewhat advanced and confident, and also very much in earnest.

“Please give me instruction,” is both a request and a subtle challenge: “I’ve heard about the great Jôshu; I’ve come seeking instruction. Let’s see what you’ve got.”

Jôshu responded, “Have you eaten your rice gruel?”

Here it might be a good idea to give some background to this question, so let’s talk a bit about life in a Chinese Zen monastery. Monks sat, ate and slept in the same spot, on the same mat, in the meditation hall. The Japanese brought this monastery life to Japan when they imported Zen in the 13th century, and it was the way we did sesshin in Kamakura. At the beginning of a sesshin, you would be issued a set of 3 nesting lacquer-ware bowls with chopsticks laid across the top, all wrapped up neatly in a large napkin. At mealtime you unfolded the napkin and put it across your lap, then received your food in two of the bowls, and reserved the third for tea, which came at the end of the meal, along with a few pickles. You drank some of the tea, then used what remained to…wash your bowls, using the pickles as a kind of small sponge, stirred about with the chopsticks. Then you drank off the rest of the tea, ate the pickles, wiped the bowls with the napkin, and tied them all up again to put them away: a remarkably efficient procedure!

Back to the koan: the monk would certainly have had breakfast with the other monks. So when Jôshu asks his question, he knows the literal answer. Moreover, he knows that the monk has not only had his gruel, but he has also washed his bowl; it’s simply part of the routine. So it’s obvious, to us and to the monk, that this dialogue is about more than breakfast. Jôshu is asking for a presentation of the monk’s understanding, which is to say a presentation of his very Self, the Self of no self.

As an advanced student, the monk knows this, but how should he answer? A “yes” could be seen as shallow and mundane, a dualistic answer without any real understanding; while a “no” would be quite clearly false.

The monk said, “Yes, I have.”

Is this a failure as an answer? Is the monk answering simply from an ordinary, dualistic point of view, or is his “Yes” a true voicing of essential reality, empty and infinite, replete with power and potential?

Over the centuries his reply has been approved by some, and criticised by others. Mumon withholds judgement, saying only,

“I hope the monk truly got it. I hope he did not mistake the bell for a jar.”

I think that because the monk is nameless, critics are unwilling to give him the benefit of the doubt, assuming that he is taking the question to be merely about breakfast. I think this is not only unfair, but also it suggests a failure to understand what I think is the point of the koan.

What about Jôshu? What does he think of the monk’s answer? Judging by his response, he finds it at least good Enôugh to warrant concluding the dialogue. Certainly he doesn’t ring his bell and send the monk packing. He says,

“Wash your bowl.”

What is Jôshu getting at here? As I said, this is very likely an advanced student, and when he asks for instruction he’s not asking about the basics. Given this, his question is not only a request to be taught, but a very subtle challenge, and I think there may well have been something in his tone or demeanor that suggested he had some degree of pride of attainment, something of the infamous Zen stink in his manner.

In any case, that is the issue that Jôshu addresses when he says “Wash your bowl”. It seems to be a perfectly matter-of-fact answer, and yet in the context of this Dharma exchange, it is much more. He accepts the monk’s answer – yes he has had his rice gruel, and yes he sees something of his fundamental self and presents it to Jôshu. Jôshu then says “Take the next step”. “Wash your bowl”.

On the mundane, every-day level, we move through the day step by step, doing what is called for – “Had your gruel? Wash your bowl”. Saturday morning? Rake the leaves. This is natural.

On the level of practice, it is good, practical advice – live step by step, moment by moment. Eat your rice; just that. Wash your bowl; just that. Do each with full attention. This is a level that any Zen student can appreciate; again, perfectly accessible.

On the level of realization, “Wash your bowl” is just “Wash your bowl.” Just this!

Just Laughing, just crying, just walking, just sitting: “Just this” wipes away all traces of Buddha and Buddhism, of Zen, and of enlightenment. Perfect freedom in the perfectly ordinary: truly wonderful!

Further, the instruction to take the next step, to “wash your bowl”, to those who have experienced kensho is an instruction to wash away the lingering smell of it, a smell that lasts as long as we are conscious of some attainment. In the most extreme cases, a student may go about proudly displaying their new-found understanding, laughing and smiling mysteriously, using cryptic expressions, setting themselves off from the ordinary unwashed public, and feeling in general a sense of superiority. This really is a zen stink, and it is the subject of many koans. (For a good example, see Case #33 in the Shoyoroku.) Working through the koan curriculum helps us to integrate insight into daily life, and at the same time to wash away the smell of attainment. In fact the two are virtually the same thing.

As Dogen says,

When you have reached this stage you will be detached even from enlightenment;

no trace of it remains, but you will practise it continually without thinking about it.

Who is that fellow in the fedora and overcoat hurrying with the crowd to catch his train? It’s Kôun Roshi, coming home from work.

The truly enlightened life is a life of nothing special, a life of eating your breakfast and washing your bowl; or in our modern lay life, of getting up at the alarm, catching the bus, sorting items into your blue boxes, taking your child to a dentist appointment. Absolutely ordinary — ordinary and miraculous.

MUMON’S COMMENT

Jôshu opened his mouth and showed his gallbladder, heart, and liver.

Jôshu reveals the whole truth, with nothing — absolutely nothing — hidden. It’s all there, whole and complete, in “Wash your bowl”.

I hope the monk truly got it. I hope he did not mistake the bell for a jar.

Even in English we say that something has the ring of truth to it. Jôshu’s bell rings perfectly true because it is one with the bell of essential reality, ringing out this whole wonderful universe. Let’s hope the monk heard it for what it really was.

I’ve already talked a bit — maybe too much — about speculation on the depth of the monk’s enlightenment. But after all, how relevant is it to us and to our own practice? The monk is a stand-in for us, so let’s leave him with our blessing, and let’s take this comment as Mumon’s best wishes for our own practice, which I think at bottom Mumon himself would say it is.

MUMON’S VERSE

Because it’s so very clear,

it takes a long time to realize.

“Look under your feet.” says the sign over the gate to the Zendo. “Nirvana is right before your eyes”, says Hakuin, in his Song of Zazen. How could you miss the Ox of enlightenment, asks another master; its horns reach to the very sky!

But this is exactly why we do miss it. It’s so close, so obvious, so ordinary, so right-in-front-of us: Just washing a bowl.

Just know that flame is fire,

and you’ll find your rice has long been cooked.

I’m not going to explain this one. It’s just too beautifully expressed to ruin it with explanations, and besides, I think they’re quite unnecessary.

Finally, there is an expression I often think of in the Sandôkai, which is a poem about the Identity of Relative and Absolute, attributed to the great master, Sekitô, a second generation teacher after Enô and a contemporary of Baso. The lines go:

Ordinary life fits the absolute as a box and its lid.

The absolute works together with the relative

like two arrows meeting in mid-air.

This koan is a beautifully simple expression of that truth. Just the ordinary washing of a bowl, fitting the absolute like a lid to a box. Much gratitude to Jôshu!