CASE

Once, in ancient times, when the World-Honored One was at Mount Grdhrakūta to give a talk, he twirled a flower before his assembled disciples. All were silent. Only Mahakashyapa broke into a smile. The World-Honored One said, “I have the eye treasury of the True Dharma, the subtle mind of nirvana, the true form of no-form, and the flawless gate of the teaching. It does not rely on letters and is transmitted outside scriptures. I now entrust this to Mahakashyapa.”

MUMON’S COMMENT

Gold-faced Gautama is certainly outrageous. He insolently degrades noble people to commoners. He sells dog flesh under the sign of mutton and thinks it is quite commendable. Suppose that all the monks had smiled—how would the eye treasury have been transmitted? Or suppose that Mahakashyapa had not smiled—how could he have been entrusted with it?

If you say the eye treasury can be transmitted, that would be as if the gold-faced old fellow were swindling people in a loud voice at the town gate. If you say the eye treasury cannot be transmitted, then why did the Buddha say that he entrusted it to Mahakashyapa?

MUMON’S VERSE

Twirling a flower,

the snake shows its tail.

Mahakashyapa breaks into a smile,

and people and devas are confounded.

DHARMA TALK

Let’s start with the characters of our story.

First, “The World-Honoured One”, the Buddha. Historically, if we accept Buddhist tradition as history, the World-Honoured One is Prince Siddhartha of the Shakya clan, born in 565 BCE in Magadha, a small kingdom in north east India . He renounced the world at 29, attained Buddhahood at 35, and died at 80, after teaching the Buddha Dharma his whole life following enlightenment. When we refer to the historical Buddha, we call him Shakyamuni Buddha, the Sage of the Shakya Clan.

Mahakashyapa was one of his main disciples, known for his strict ascetic discipline and his emphasis on the precepts. Like the Buddha, he was of noble birth, but, confronted with the reality of suffering, he determined to find a teacher, and so he walked into the forest, still wearing his rich robes. He came upon a man sitting at the foot of a tree and instantly knew that this was his teacher. It was the Buddha, with whom Mahakashyapa insisted on exchanging his fine robes for the Buddha’s rags.

Mount Grdhrakuta is a mountain in Magadha, full of caves, and the caves full of hermits and ascetics. There the Buddha gave many of his talks. An easier name than this mouthful of consonants is “Vulture Peak”, or “Mount Eagle”, so-called because of its shape.

Here is the koan again. Consider its theme and its “pivot points”.

Once, in ancient times, when the World-Honored One was at Mount Grdhrakūta to give a talk, he twirled a flower before his assembled disciples. All were silent. Only Mahakashyapa broke into a smile. The World-Honored One said, “I have the eye treasury of the True Dharma, the subtle mind of nirvana, the true form of no-form, and the flawless gate of the teaching. It does not rely on letters and is transmitted outside scriptures. I now entrust this to Mahakashyapa.”

Clearly the general theme is transmission from teacher to student, in this case the very first transmission, from the Buddha to Mahakashyapa.

What is transmission? How are we to think of it? Normally, of course, we think of transmission as the conveying of something – information, energy, a physical object — from one person or place to another. But it’s not hard to see that Zen transmission must be very different; certainly Zen realization is not something that can be conveyed from one person to another. It’s not an insight in that sense.

Transmission is a process. It begins with authentic realization, direct experience of our own fundamental reality, transcending subject and object. This is followed by confirmation by the teacher of the authenticity of the student’s realization, that it is the same realization of this empty, infinite, dimensionless Now as that experienced by the entire lineage of teachers, going back to Shakyamuni Buddha himself. This is then followed by a formal acknowledgement before the sangha of the fact that the experience of the teacher and that of the student are in accord with each other, each founded on genuine realization of the essential reality of Buddha Nature, and that therefore the student is now in a position to teach others.

This process maintains the authenticity of the teaching in the ongoing lineage. In this case of Buddha twirling a flower, whether it actually happened this way or not, the three phases of transmission have been condensed into this one brief story, making it the absolute ideal: realization, itself a kind of transmission, confirmation, and formal acknowledgement before the sangha: all happen practically in the same moment.

Realization cannot be conveyed to us by someone else, and yet there is transmission. This koan presents us with an image of it in a story that challenges us to attain transmission ourselves.

Remember, there is not a single koan that is not about you, not one whose purpose is not to bring you to realization, or to deepen realization that you’ve already had. Some koans are records of historical events and exchanges, while some, like this one, are mythic in nature. It could be said, in fact, that all koans are mythic, as even the ones based on historical fact have been pruned and shaped so as better to serve their purpose, which is to be both spiritual guide and challenge. This koan, the story of the transmission from the Buddha to Mahakashyapa, did not appear until 11th century Song China. It’s value as a teaching tool, however, was recognized very quickly and it was immediately widely adopted in Zen circles and incorporated into koan collections, such as the Mumonkan, that were being compiled at that time.

As a myth created for the purpose of nudging you toward enlightenment, it challenges you to find your way through a treacherous net of delusory concepts and assumptions, which Mumon delights in pointing out in his ironic way, to help you find your way to the other side. At the same time it points up the crucial role transmission plays in the Zen lineages. How important is it? It started with the Buddha himself and the succession since then is unbroken.

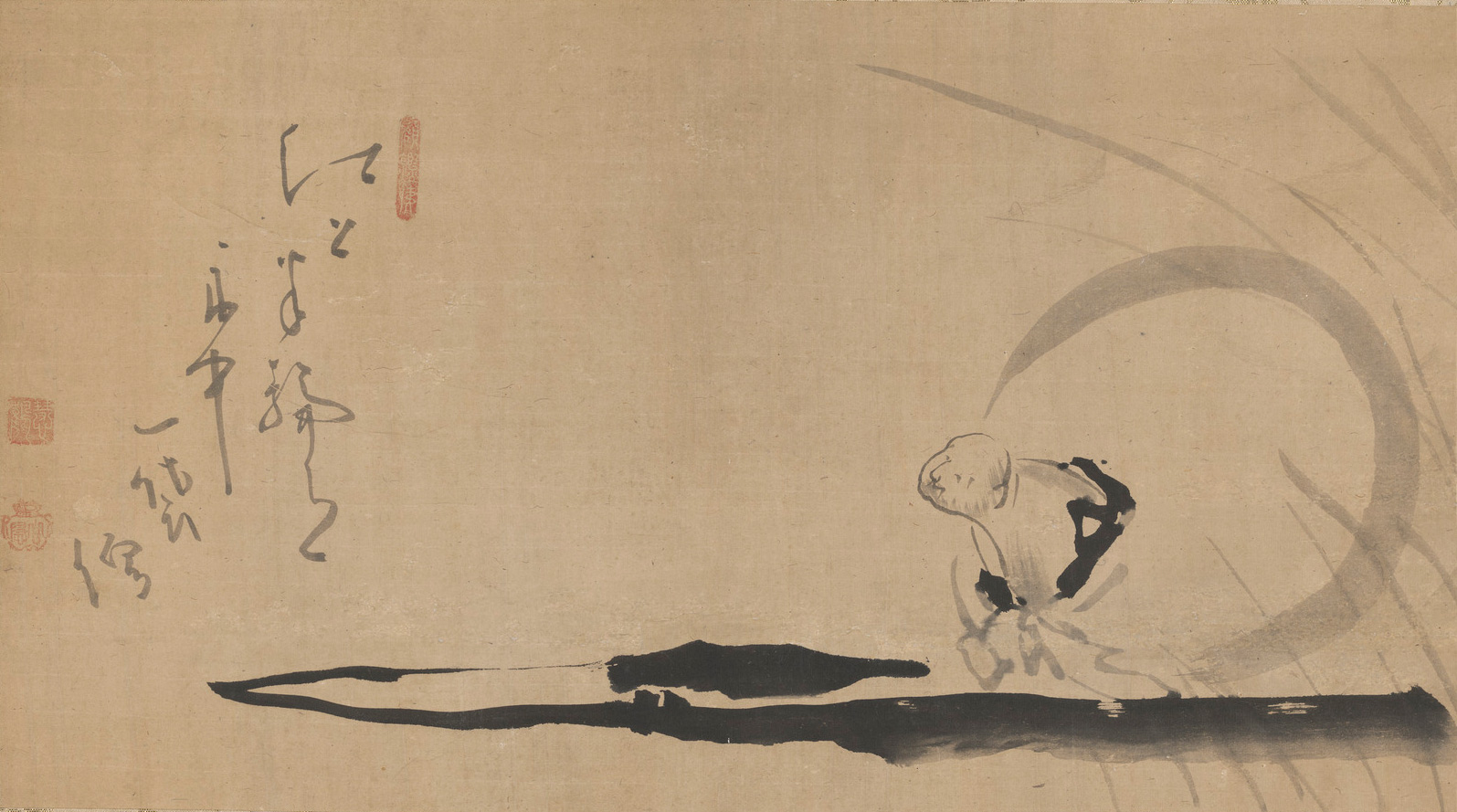

Let’s begin with the flower. The Buddha held up a flower, just as Gutei held up a finger, Joshu said Mu, Rinzai gave a shout, Tokusan gave a blow, and countless teachers have held up fly whisks, staffs and kotsus. Anything at hand would do, but flowers seem to have a particular power as a kind of universal icon of the simple mystery of life and the universe. “To see a World in a Grain of Sand, and Heaven in a Wild Flower”, wrote William Blake, while Tennyson contemplated the “Flower in the Crannied Wall” in an attempt to fathom God and man.

Some say it was a lotus that the Buddha held up. Whether that is something that appears somewhere in some original text I don’t know, but it doesn’t appear in the koan as it has come down to us, and I think it may simply be an assumption based on the lotus’s central role in Buddhist iconography. I hope that’s the case, because to me it’s important that the Buddha’s flower be nothing special, nothing grand: not a lotus, not a chrysanthemum, more like a daisy, something simple, humble, quiet and understated, as in fact a flower plucked from the ground on the side of a mountain was very likely to be.

Which brings us to Mahakashyapa’s smile, and gives it added significance. He alone notices this modest flower, and … and what? What is it that he sees? What is it that he experiences? Why does he smile? Apparently, the Chinese words literally mean “his face cracked”. That’s quite a smile! That sounds like real joy, the joy of sudden realization.

Here are words quoted by Zenkei Shibayama from an unnamed “old Zen master”:

As I see it with my mind of no-mind,

It is I-myself, this flower held up.

So…why did Mahakashyapa smile? If you can see this, you’ve got the koan. And to see this, you must see the flower as Mahakashyapa saw it: not just heaven, as in William Blake’s verse, but heaven, earth, sun, moon, stars and he himself, the entire universe coming forth in this unassuming little flower.

And now to the formal transmission:

I have the eye treasury

The “eye” of the eye treasury is the third eye, the eye which sees our essential reality, as contrasted with conceptual understanding, which sees only a conceptual shadow of essential reality.

of the True Dharma,

The Truth of the empty and infinite essential nature of the universe, and also the ongoing unfolding of Buddhism in this world.

the subtle mind of nirvana,

the mind that is perfectly empty, perfectly free, and endlessly creative

the true form of no-form,

Straight from the Heart Sutra:

Shariputra, form is no other than emptiness, emptiness no other than form; form is exactly emptiness, emptiness exactly form.

and the flawless gate of the teaching.

The gate of perfect emptiness out of which all teaching arises. Can perfect emptiness be anything but flawless?

It does not rely on letters and is transmitted outside scriptures.

These are pretty much an exact echo of Bodhidharma’s words, which, not so coincidentally, were codified about the same time, each of them – Buddha and Bodhidharma – being made to articulate what had already served for centuries as a founding principle of the Zen sect.

I now entrust this to Mahakashyapa.

And the Buddha entrusts it to you, in turn, when you “see” the flower the way Mahakashyapa sees it; when you can smile with Mahakashyapa’s smile, your face cracking with joy, arising from your perfect intimacy with that flower. You can then experience the joy of the transmission of the un-transmissable, entrusted to you as well as to Mahakashyapa, your mind in perfect accord with those two ancient ones, and with all the rest of the lineage.

Mumon’s Comment

Gold-faced Gautama is certainly outrageous. He insolently degrades noble people to commoners.

Not only the assembly on Vulture Peak, but you and I as well, are the noble people, intrinsically Buddhas ourselves, who are degraded by this great show of transmission to Mahakashyapa. What does he have that we don’t have? Good question!

He sells dog flesh under the sign of mutton and thinks it is quite commendable.

Dog flesh! Nothing more common, in ancient China, at least. But he goes through all this rigmarole of pretending that it’s high class mutton. Essential nature is who and what we are; what could be more common? Yet he makes this great, high falutin’ show of “transmitting” the eye treasury, the True Dharma, the subtle mind of nirvana, and on and on….

Suppose that all the monks had smiled—how would the eye treasury have been transmitted?

What is transmission!? Remember, every koan is about you….

Or suppose that Mahakashyapa had not smiled—how could he have been entrusted with it?

Again, what is transmission!? What is it that is being transmitted? And to whom?

If you say the eye treasury can be transmitted, that would be as if the gold-faced old fellow were swindling people in a loud voice at the town gate.

The famous Australian cartoonist, Michael Leunig, had a cartoon which depicted two birds standing on a chair, looking across a desk to a man in a checked suit wearing a bird mask. Above the man there’s a sign taped to the wall: “Larry Seed, Real Estate Agent to Birds/ Sky Sale Now On”. Don’t be fooled, says Mumon.

If you say the eye treasury cannot be transmitted, then why did the Buddha say that he entrusted it to Mahakashyapa?

The Japanese haiku poet, Matsuo Basho, who was himself a lay Zen student, has a poem:

To bird and butterfly

There is an unknown flower:

The autumn sky.

Though Buddha nature is the essential nature of every being, it is recognized and realized by relatively few. Consciously at least, most of us never even suspect the existence of that unknown flower, and we are too obsessed with chasing delusions to pay any attention to any intuition that we might have of it. Thank goodness for the Buddha and his successors, from Mahakashyapa down through the whole lineage, all those who have seen it, who have heard it, who have received and maintained it, that it might come to us in turn.

MUMON’S VERSE

Twirling a flower,

the snake shows its tail.

Archetypally, snakes represent creative life force. Because they shed their skin they are symbols of rebirth and transformation. Moreover, the ouroboros, the snake that swallows its own tail, is an archetype of eternity, and a Chinese dragon, in form at least, is a next-level snake.

Remember the ox herding pictures? In an early one, after following the tracks for a while, the herder spots the ox’s horns, rising above a thicket. Spotting the horns, he knows that the ox is there. Likewise, here, seeing the snake’s tail, we know that the snake — transformation, renewal, and, ultimately, eternity — is there. Where is the tail? Buddha twirled a flower; Mahakashyapa smiled.

Mahakashyapa breaks into a smile,

and people and devas are confounded.

People and devas and many generations of Zen students, have been confounded, but with dedicated zazen, they have come to smile with Mahakashyapa and with all those who have come to see the Buddha’s flower as it really is, who have become intimate with it. This koan is an invitation to join them.