CASE

Once when Hyakujô gave a series of talks, a certain old man was always there listening together with the monks. When they left, he would leave too. One day, however, he remained behind. Hyakujô asked him, “Who are you, standing here before me?” The old man replied, “I am not a human being. In the far distant past, in the time of Kāśyapa Buddha, I was head priest at this mountain. One day a monk asked me, ‘Does a fully enlightened person fall under the law of cause and effect or not?’ I replied, ‘Such a person does not fall under the law of cause and effect.’ With this I was reborn five hundred times as a fox. Please say a turning word for me and release me from the body of a fox.” He then asked Hyakujô, “Does an enlightened person fall under the law of cause and effect or not?” Hyakujô said, “Such a person does not evade the law of cause and effect.” Hearing this, the old man immediately was enlightened.

Making his bows he said, “I am released from the body of a fox. The body is on the other side of this mountain. I wish to make a request of you. Please, Abbot, perform my funeral as for a priest.” Hyakujô had the head monk strike the signal board and inform the assembly that after the noon meal there would be a funeral service for a priest. The monks talked about this in wonder. “All of us are well. There is no one in the morgue. What does the teacher mean?”

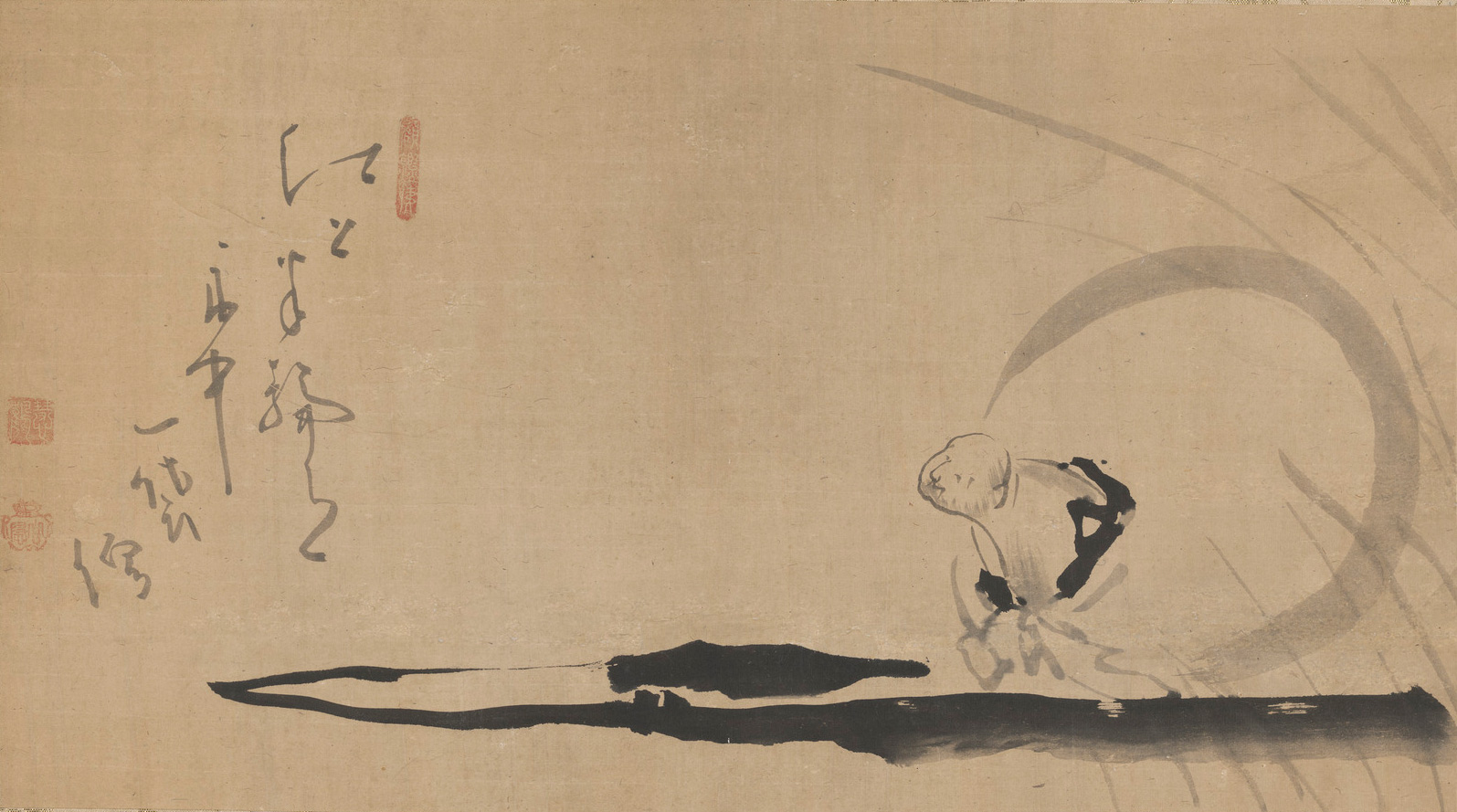

After the meal, Hyakujô led the monks to the foot of a rock on the far side of the mountain. And there, with his staff, he poked out the body of a dead fox. He then performed the ceremony of cremation.

That evening he took the high seat before his assembly and told the monks the whole story. Ôbaku stepped forward and said, “As you say, the old man missed the turning word and was reborn as a fox five hundred times. What if he had given the right answer each time he was asked a question—what would have happened then?” Hyakujô said, “Just step up here closer, and I’ll tell you.” Ôbaku went up to Hyakujô and slapped him in the face. Hyakujô clapped his hands and laughed, saying, “I thought the Barbarian had a red beard, but here is a red-bearded Barbarian.”

MUMON’S COMMENT

“Not falling under the law of cause and effect.” Why should this prompt five hundred lives as a fox? “Not evading the law of cause and effect.” Why should this prompt a return to human life? If you have the single eye of realization, you will appreciate how the old Hyakujô lived five hundred lives as a fox as lives of grace.

MUMON’S VERSE

Not falling, not evading—

two faces of the same die.

Not evading, not falling—

a thousand mistakes, ten thousand mistakes.

TEISHO

Most koans involve a record of an exchange between 2 masters, or a master and student, but some, like this one, involve myth or folklore. It’s important to remember that if there is a supernatural element, as there is here, it is never the point of the koan, but merely a device in the service of bringing students to realization, so it’s not necessary to believe in ghosts or gods to get the point of the koan.

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

The three characters of this koan are as follows:

Current Hyakujô, former student of Baso, and so brother in the Dharma to Nansen, who was Joshu’s teacher. His dates are 720-814, the height of the Tang empire. The name, Hyakujô, like the names of other Chinese Zen Masters, is taken from the name of the mountain on which his temple resides, and so in fact he is one in a series of Hyakujô’s.

Former Hyakujô, the old man of the story, was the master of the same temple on the same mountain, but from a previous kalpa, or eon, the time of Kasyapa Buddha, and so a mythical time. We meet Former Hyakujô as a soul, come to beg release from the body of a fox, in which he has been compelled to live for 500 lives as the karmic consequence of misleading a disciple in his pursuit of the Dharma.

Ôbaku, a major disciple of Hyakujô, and teacher, in turn, of Rinzai, the founder of one of the two lines of Zen that survive to this day.

And so to the koan. When dealing with any koan it’s important to determine its central point. So what is the nub of the first section of this koan? Of course, it is the question, “Does a fully enlightened person fall under the law of causation, the law of karma?” Seems rather abstract doesn’t it? Something for Buddhist scholars to discuss over tea. But put another way, it turns out to be exactly the question at the core of Zen practice: Can we ever be free of karma? Can we ever be free?

In classical Buddhism, karma is the relentless law of cause and effect that determines our life situation, for good or ill. It is represented in Buddhist imagery as an infinite net, the Net of Indra, of which each node is an individual confluence of space and time that we call a phenomenon: the flap of a butterfly wing, a heart attack, a wedding, an exploding star: each the effect of some cause or network of causes and conditions, and each itself a cause with further effects that ripple out through the rest of the net, the vivid image of the Buddhist doctrine of interdependence, or “dependent arising”.

So karma is not just an individual matter, like the notion of “sin” in much contemporary Christianity. It’s also broadly communal, if we can use that word to refer ultimately to the community of all beings throughout space and time as they cycle through the six worlds , to put it in classical Buddhist terms. The six worlds are heaven, the world of divas, the world of humans, the world of animals, the world of hungry ghosts, and at the bottom, the lowest of the worlds, hell. All are driven by the desires that arise out of the delusion of a separate self opposed to all that is seen as “other”. This constant cycling is characterized by the profound unease called “dukkha”, usually translated as “suffering”, as in, “Life is suffering”; and the essential freedom Buddhism offers us is freedom from delusion, freedom from desire, and therefore freedom from karma and dukkha.

On the surface, according to Buddhist doctrine, the answer to the monk’s question, “Does a fully enlightened person — i.e. a buddha — fall under the law of causation, or karma?” must surely be “No, he does not”. Obviously! And yet this answer, it seems, is so grievously wrong that Former Hyakujô winds up living five hundred lives as a fox. But what if he had answered “Yes”? Would that then be the correct answer? Must we say then that even a Buddha is subject to the laws of karma? Surely that’s a denial of the very definition of “Buddha”! In fact, had he answered “Yes” he would have ended up living exactly the same five hundred lives as a fox. Wrong again!

Grappling with this question, do not think of individuals or communities as being affected by, or even determined by karma, because to do so is to fall into the delusion of a separate self from the very start. Rather, think of them, and of you yourself, as karma itself; the vast Net of Indra as your very substance! And remember the essential message of the Heart Sutra: “Form is Emptiness; Emptiness is Form!”

So…why a fox? The fox in Asian folklore is much like the one in Western folklore: clever and wily, though with an edge of malice that the more sympathetic Western version doesn’t possess. In Zen stories, “fox”, or “wild fox spirit”, is generally an epithet denouncing someone’s understanding as merely superficial and clever, not genuine insight. So in this case, Former Hyakujô’s penalty for misleading a student of the Dharma by answering the question out of his own superficial understanding, is to have his nose rubbed in the fact of his own glibness.

Current Hyakujô’s answer by contrast is “He does not evade causation”. Is there a difference between that answer and “Yes, he is subject to the law of causation.” What would the difference be?

In any case, Former Hyakujô hears and comes to a sudden realization of the truth, which releases him from the body of the fox.

What is it that he realizes? Why is “No” wrong? Why is “does not evade” right? Look at the comment and the verse for help. What is it that Former Hyakujô realizes? Again, remember, “Form is emptiness; emptiness is form”.

Now to the brief second section of the koan.

Current Hyakujô digs out the body of a fox and buries it as a priest, thus honouring the Former Hyakujô’s request. Under the terms of the story so far, this seems reasonable. So why, a thousand years later, does the great Japanese master, Hakuin Zenji, criticize Current Hyakujô, saying, “What are doing, old Hyakujô, performing a funeral for a fox as though it were a priest?”

Consider this point carefully. Are they burying a priest or a fox? What after all is the point of the koan? Listen to Mumon’s comment: “If you have the single eye of realization, you will appreciate how old Hyakujô lived five hundred lives as a fox as lives of grace.” Why bury the fox as a priest? Is there anything lacking in the fox as a fox?

Sentient beings are numberless; I vow to free them.

Last winter, on a late January evening, I heard a fox barking in the woods behind our house. I stood still and listened as he barked on for a full five minutes. How do you think I should free him?

And so to the third section of the koan: Ôbaku’s challenge and response.

He asks Current Hyakujô, What if he had given the right answer each time he was asked a question?

Not just this particular question – any question pertaining to the Dharma. What if he had never made any mistakes of any sort? What then? Would things have been different? Would he himself have been different? In other words, is there then some essential difference between the fully enlightened person and the one who makes mistakes? Like you? Some essential difference between Buddha and you? Remember Bodhidharma’s response when asked what is the holy truth of Buddhism: all vastness, nothing holy. All vastness is me; all vastness is you; all vastness is Hyakujô, current and former; all vastness is the fox, all 500 lives of him.

Hyakujô says “Just come here and I’ll tell you.” Clearly he’s up to no good – probably getting his staff ready for a good swat, but Ôbaku, who himself is a great master, the dharma father of Rinzai, beats him to it, stepping up and swatting Hyakujô. To Hyakujô, this is a delightful confirmation of the depth of Ôbaku’s enlightenment. He claps his hands, laughs a great laugh and says, “I thought the barbarian had a red beard, but here is a red-bearded barbarian.”

The barbarian is the come-from-away Bodhidharma, who, legend has it, had a red beard. “I thought the barbarian had a red beard” …. All this time I’ve known the story of Bodhidharma…. “But here is a red-bearded barbarian!” But my goodness, here he is in the flesh! Understand that though this is in one sense a metaphor — Ôbaku is not Bodhidharma — in a deeper, essential sense, it is not a metaphor at all, and not hyperbole. Hyakujô means exactly what he says. All vastness, nothing holy is Bodhidharma; all vastness, nothing holy is Ôbaku.

We could discourse further on the meaning of this koan, but I think nothing sums up the koan, or points us to its import for us and our own lives, like Mumon’s wonderful blessing of a verse:

Not falling, not evading —

two faces of the same die.

Not evading, not falling —

a thousand mistakes, ten thousand mistakes.

Leonard Cohen would add, “Hallelujah!”